A book about extreme violence, inhuman behavior, and brutality, that begins with a heartfelt: “I love you”—how impossible is that? When he was thirteen years old, George Perry Floyd, Jr., put his hand on his sister, Zsa Zsa’s wrist, and said, “‘Sis, I don’t want to rule the world; I don’t want to run the world. I just want to touch

the world.’”

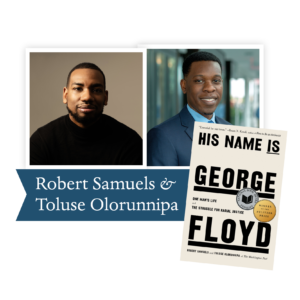

Washington Post reporters Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa set out to understand how George Floyd’s life had unfurled and what battles he had to fight against the justice system and the police. And what battles he fought on behalf of others.

“I can’t breathe.” When a police officer shoved his knee onto George Floyd’s neck, for allegedly trying to pass a counterfeit $20, Floyd pleaded for his life. For nine minutes and 29 seconds, the officer pushed down hard on a shackled man whose face was mashed onto the street. For the last two minutes Floyd was motionless, without a pulse.

George Floyd, born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, was often in charge of his four siblings. The family, who couldn’t afford laundry detergent, washed their clothes in the sink with dish soap. Floyd, who grew to be a gentle giant, played high school basketball, then college football when his family moved to Houston. He struggled with fentanyl and amphetamines and was arrested eight times for drug possession, theft, and trespass—while constantly trying to get clean. Even leading his religious group once he moved to Minneapolis. But Samuels and Olorunnnipa document that he was always on the police radar.

The shocking revelations are laid out in a clear-eyed, even-toned manner. Readers learn that in a privately run federal prison where Floyd was sent when he was convinced to accept a plea deal for armed robbery—not his M.O.—he had to pick cotton from sunup to sundown without pay, a “master” riding a horse through the fields, inmates serving as “house boys” to the owner of the prison.

Meticulous reporters, Samuels and Olorunnipa, conducted more than 400 interviews for this book, making sure to confer confidentiality whenever asked. Their fact finding is moving, telling, startling. When the authors compared notes of family members with those of historical records, the family members’ remembrances proved to be absolutely on target. These authors confirm that people are telling the most difficult truths. Truths to power. Truths despite cruelty. Truth.

They document the extraordinary reverberations. After Floyd’s death thousands gathered for what is purported to be the largest civil rights march since the Civil Rights Era. George Floyd murals appeared in cities around the country. Colleges and universities set up scholarships in his honor.

Yes, in this brilliant book, His Name is George Floyd, Samuels and Olorunnipa teach us so much about what goes on between races. Between police, the justice system, and humans who get entangled in their webs. Yes, George Floyd, who gave his life, touched the world.

– Lou Ann Walker,

2023 Nonfiction Judge

We are a weary, footsore, ragged army taking our needed rest after fifty-six straight days of fighting. I will not write to you of battles: no doubt you read of them in the New York press. They say we are winning this war. They say it, and yet that word does not carry the same meaning to me as it once did. This does not feel like winning, even when the shooting stops and the cannons fall silent and I stand up with my head ringing in the midst of shattered trees and shattered bodies and can count more of us alive and more of them dead.

We are a weary, footsore, ragged army taking our needed rest after fifty-six straight days of fighting. I will not write to you of battles: no doubt you read of them in the New York press. They say we are winning this war. They say it, and yet that word does not carry the same meaning to me as it once did. This does not feel like winning, even when the shooting stops and the cannons fall silent and I stand up with my head ringing in the midst of shattered trees and shattered bodies and can count more of us alive and more of them dead.

For as long as anyone can remember,

For as long as anyone can remember,

American’s version of democracy is far from perfect,

American’s version of democracy is far from perfect,