Bio

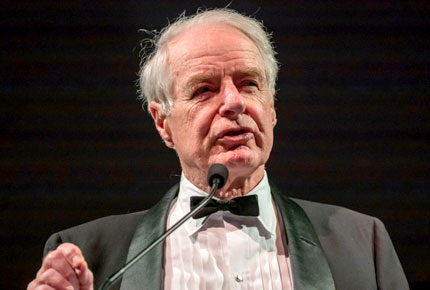

Born in Columbus, Ohio, and educated at Miami University, Wil Haygood has traveled the world as a journalist writing about war, peace, and political activism for The Pittsburg Post-Gazette, The Boston Globe, and The Washington Post. He covered the coal industry, was taken hostage by Somali rebels, and covered war zones in Nigeria and India. He covered apartheid in South Africa and witnessed the release of Nelson Mandela. He covered the Los Angeles Riots, slipped into a prison to interview soul-singer James Brown, spent 40 days in Louisiana covering Hurricane Katrina, and covered the first presidential campaign of Barack Obama. He has been honored with numerous awards for his reporting.

For the last three decades his books have captured the sweep of American culture focusing on the rarely or never-told stories of the Black experience with the in-depth analysis that this nation so desperately needs. His books began with personal stories of a trip down a river, and a coming-of-age memoir of his growing up in Columbus. They then begin to range out into biographies of Black politicians, entertainers, and sports figures who have carved out a place in history in the name of justice: Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. helped President Johnson pass the War on Poverty legislation; Sammy Davis Jr., was a major financial backer of the MLK March on Selma; Sugar Ray Robinson, worked to secure financial rights for fighters. Like Haygood himself, each subject used his particular talents to bring us closer to justice and peace.

His book The Butler about Eugene Allen, who served eight presidents at the White House, became an award-winning film that was number one at the box office for weeks. His next three books are familiar to the DLPP audience, Showdown, a DLPP finalist focused on the contentious 1967 battle to get Thurgood Marshall onto the Supreme Court; Tigerland picked up the next two years, 1968 and 1969 and followed Black athletes as they captured two state titles in Columbus, Ohio. His most recent book Colorization takes a century-long look at decades of Hollywood’s handling of g the dreams of Black actors, actresses, writers and directors. His books have won multiple awards.

Wil Haygood has been the recipient of multiple fellowships including a Guggenheim Fellowship and a National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship. He has received Honorary Degrees from Loyola, Ohio Wesleyan, Hood College and Goucher College and his own alma mater Miami where he received the Presidential Medal, the highest honor the university bestows and where a street on campus was name Wil Haygood Lane, which is where the Freedom Summer volunteers gathered before they headed south to Mississippi to register Black voters and where James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner – were subsequently murdered by Klansmen. In 2019, Wil became the writer in residence for the Roger Brown Residency in Social Justice, Writing, and Sport at the University of Dayton.

In 1957 Congressman Adam Clayton Powell

In 1957 Congressman Adam Clayton Powell

porch. Beside her, a bushel basket of ripe peaches or tomatoes. The drunkards buzzing, but easily smashed with a swat. Early mornings, she starts singing, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” and that’s your cue to rise. To eat the heavy breakfast that will keep you full all day. Once you’ve helped her with peeling those tomatoes or peaches, there are weeds to be plucked from the garden, from around the vegetables that will show up fresh on the supper table. Fish need cleaning if Uncle Norman comes through with a prize. After dinner, the piecing together of quilt tops from remnants until the light completely fades. The next morning, it starts again. A woman singing off-key praises to the Lord. The sweet fruit dripping with juice. The sound of bugs.

porch. Beside her, a bushel basket of ripe peaches or tomatoes. The drunkards buzzing, but easily smashed with a swat. Early mornings, she starts singing, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” and that’s your cue to rise. To eat the heavy breakfast that will keep you full all day. Once you’ve helped her with peeling those tomatoes or peaches, there are weeds to be plucked from the garden, from around the vegetables that will show up fresh on the supper table. Fish need cleaning if Uncle Norman comes through with a prize. After dinner, the piecing together of quilt tops from remnants until the light completely fades. The next morning, it starts again. A woman singing off-key praises to the Lord. The sweet fruit dripping with juice. The sound of bugs.

That’s how it will be, right? When they find my note later this morning. Everyone tracing back through my life, looking for devil markings on my skin. I’ve been doing it too. For days, I’ve felt tender spots on my scalp like horns might be pushing through. But I keep thinking about something Mr. Balch said last spring when we were walking back from meeting.

That’s how it will be, right? When they find my note later this morning. Everyone tracing back through my life, looking for devil markings on my skin. I’ve been doing it too. For days, I’ve felt tender spots on my scalp like horns might be pushing through. But I keep thinking about something Mr. Balch said last spring when we were walking back from meeting.

To follow Dasani, as she comes of age, is to follow

To follow Dasani, as she comes of age, is to follow