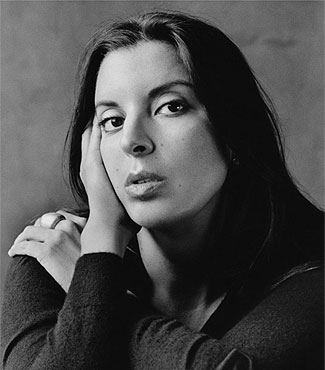

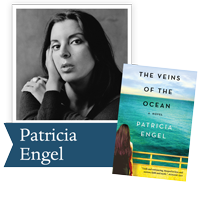

Patricia Engel’s most recent novel, The Veins of the Ocean, was published in May 2016 by Grove Press and named a New York Times Editors’ Choice and a Best Book of the Year by the San Francisco Chronicle, Electric Literature, and Entropy.

Vida, her debut, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, winner of the Premio Biblioteca de Narrativa Colombiana, a Florida Book Award, International Latino Book Award, and Independent Publisher Book Award, and a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Fiction Award, New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, and Paterson Fiction Award. Additionally, Vida was long-listed for The Story Prize, named a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and a Best Book of the Year by NPR, Barnes & Noble, Latina Magazine, and Los Angeles Weekly. Her novel, It’s Not Love, It’s Just Paris, was winner of the International Latino Book Award and an Elle Reader’s Prize, and recommended by the Los Angeles Times, Time Out New York, and Flavorwire.

Patricia’s books have been translated into many languages and her short fiction has appeared in The Atlantic, A Public Space, Boston Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, Harvard Review, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere, and anthologized in The Best American Short Stories 2017 and The Best American Mystery Stories 2014. Her essays and reviews have appeared in the New York Times, Virginia Quarterly Review, Catapult, and numerous anthologies. She has received awards including the Boston Review Fiction Prize, fellowships and residencies from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Key West Literary Seminar, Hedgebrook, Ucross, the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs, and a 2014 fellowship in literature from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Born to Colombian parents and raised in New Jersey, Patricia currently lives in Miami. She teaches creative writing at the University of Miami and is Literary Editor of the Miami Rail.