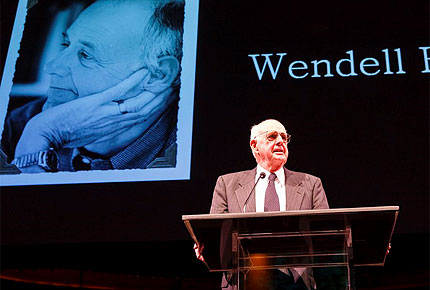

Wendell Berry has been compared to Thomas Jefferson, for his wisdom in land management; to Edward Abbey, for his condemnation of projects that upset the balance of nature; to Thoreau, for his appreciation of the natural world; and to Wallace Stegner, for his sense of place. The essayist, philosopher, poet, professor, and novelist has also long been known as a proponent of peace, one who hates every war, including “good” ones.

Not only do his books reflect the love of peace that is the absence of war, but other kinds of peace, as well. The peace of mind from knowing who we are and where we come from figures prominently in his work.

When it comes to “where we come from,” Wendell and I have much in common. My brother-in-law is from Wendell’s beloved Henry County, and his sister married a Berry—but no relation. Wendell and I were born just a few months apart. When he was entering the University of Kentucky, I was enrolling at the University of Louisville. We both have deep roots in rural Kentucky, his in Henry County, mine in Larue County, about 100 miles and about two hours apart. We both had grandfathers who had general stores.

And yet, while he has drawn on a rich lode of memories for literary inspiration, I would have described my numerous childhood visits from Louisville to Larue County’s Buffalo as long episodes of boredom; I longed for exotic faraway places. It is only in later years that I can truly appreciate the past and see that the Buffalo folks, very much like those of his fictional Port William, were not boring at all.

Consider my maternal grandmother, who, at 17 and an only child, under the pretext of visiting a cousin took the buggy and left her small Catholic community to elope with my Protestant grandfather. . . My paternal Granddaddy Brown, a deputy sheriff, told of escorting a murderer to prison, sharing a hotel room bed on the way, as was the custom. He claimed he wasn’t afraid, but he did sleep with a gun under his pillow. . . . Love affairs, tragedies and joys—all the dramas of life were played out there.

Wendell’s descriptions of rural Kentucky ring so true that I am struck by a jolt of recognition, and I want to shout, “Yes, that’s the way it was!” I grew up hearing stories of the Great Flood of 1937, featured so prominently in

Jayber Crow. The 1918 flu epidemic that carried off Jayber’s parents also killed my mother’s baby brother and her pregnant sister’s husband. The accents he records were the same; I had forgotten how my grandmother spoke of “ahrning” clothes. Like the grandmothers in his books, she, too, made her own soap; the bucket of lye was a fearsome thing. There was the same put-down humor, which my sister and I called “Buffalo humor,” and the same kind of relations between the races. Those, although not equal, were at least personal. Once when “Aunt Cissy,” an African American, came to visit, I must have smarted off in some way and was told in no uncertain terms that Aunt Cissy was my grandmother’s friend, and I was to show her respect.

There was the same sense of community in Buffalo as in the fictional Port William, a closeness which would bring my parents back to “the old home place” so often. And there was the same love of the land that kept my father coming back on weekends to check on his farm, while we waited interminably in the car.

My grandfather’s general store seems to have been peopled by the same farmers as Wendell’s grandfather’s, who played checkers close to the pot-bellied stove in the winter and drank with a dipper from the water bucket. I wonder if the stores smelled the same—a mixture of tobacco, cheap candy, dyed cloth, and dried peaches. And I wonder if, he, too, sneaked lumps of sugar out of the sugar barrel.

Andy Catlett in the book of that name echoes my thoughts when he says, “Now I can wish that I had foreseen then what I would want to know now, and had asked the questions I now wish I had asked.”

Although Wendell would prefer to be known as an agrarian writer rather than an environmentalist in the traditional sense, best of all are his descriptions of nature, seen through the prism of a poet. “Here on the river,” says Jayber Crow, “I have known peace and beauty such as I never knew in any other place. . .”

Waterways hold a special place in his books, in fact they seem to take on a life of their own. In

Hannah Coulter the water “comes down in a hurry, tossing itself this way and that as it tumbles among the broken pieces of old bottom. The stream seems to be talking. . .” In

Jayber Crow “the river seems to be holding itself up before you like a page opened to be read. There is no knowing how the currents move. They shift and boil and eddy. . . .” And at Coulter Branch, where “the water fell with a hundred voices down steps and glides among the rocks from pool to pool, where the mosses were bright green on the rocks and the tree roots and the stonecrop was in bloom, we saw a red fox step out of the undergrowth into a shaft of sunlight where he paused, a moment, glowing, and disappeared like a flame put out.”

I have traveled to the Red River Gorge many times, but it was not until reading

The Unforeseen Wilderness, written to protest the planned construction of a river-dooming dam, that I realized that I have looked without seeing and heard without listening. We enter a magical place when we read that in the gorge he found “a little dell in the woods where several streams met, making a pattern like a chicken track. The air opened and grew spacious under great hemlocks and beeches; shafts of sunlight slanted in as thick as the tree trunks. . .” At another spot, hearing “warblers singing everywhere,” he writes, “We linger over the rock gardens along the shores, examining their growth of lichens and moss and liverworts, violets and bluets and rue. The laurel bushes that here and there overhang the banks are in bloom. . . In front of us there is a series of narrow ledges, divided by sheer high falls of the rock. From the top ledge, high up against the sky, a little stream leaps and slides, glittering and spattering, until finally it is gathered again in to the tidy stream at our feet. The ledges are all covered and hung with flowers and mosses and ferns. On the other sides of the opening the forest rises tall and densely green. It is the wildest of places . . . “

And, finally,

The Peace of Wild Things is a lesson in serenity:

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s

lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and

the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief.

I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting for their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

– Nancy Brown Diggs