Bio

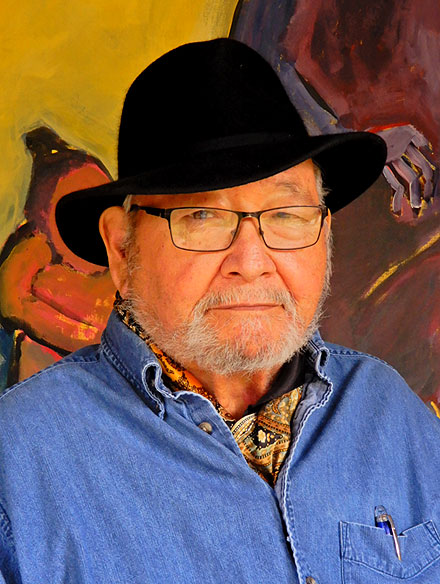

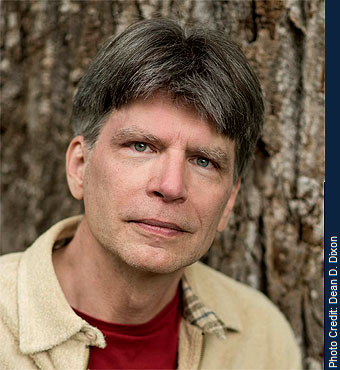

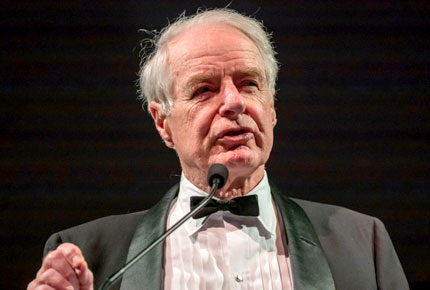

Scott Momaday is a poet, a Pulitzer prize-winning novelist, a playwright, a painter and photographer, a storyteller, and a professor of English and American literature. He is Native American (Kiowa), and among his chief interests are Native American art and oral tradition. He received the National Medal of Arts in November 2007 “for his writings and his work that celebrate and preserve Native American art and oral tradition.” In addition to the National Medal of Arts, he has received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his first novel, House Made of Dawn, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Institute of Arts and Letters Award, the Golden Plate Award from the American Academy of Achievement, the Premio Letterario Internazionale “Mondello”, Italy’s highest literary award, The Saint Louis Literary Award, the Premio Fronterizo, the highest award of the Border Book Festival, the 2008 Oklahoma Humanities Award, and the 2003 Autry Center for the American West Humanities Award. UNESCO named him an Artist for Peace in 2003, the first American to be so honored since the United States rejoined UNESCO. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds 20 honorary degrees from colleges and universities including Yale University, the University of Massachusetts, the University of Oklahoma and the University of Tulsa in his home state of Oklahoma, Blaise Pascal University (France) and his alma mater, the University of New Mexico. In 2018 he received the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Book Award. In 2019 he was inducted into the Native American Hall of Fame. In 2019 he was named the recipient of the Prairie Reserve Ken Burns American Heritage Prize.

Momaday was born in Lawton, Oklahoma, and was raised in Indian Country in Oklahoma and the Southwest, where his parents, artist Al Momaday and writer Natachee Scott Momaday, were teachers employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He graduated from the University of New Mexico (BA 1958) and Stanford University (MA 1960, PhD 1963). He has held tenured appointments at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University, and retired as Regents Professor at the University of Arizona. He was the first professor to teach American literature at the University of Moscow in Russia in 1974, and was the inaugural University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Northern Momentum Teacher/Scholar in 2001. He is presently a Senior Scholar at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

His books have been translated into French, German, Italian, Russian, Swedish, Japanese, and Spanish and include The Complete Poems of Frederick Goddard Tuckerman (Oxford University Press), House Made of Dawn (Harper and Row), The Way to Rainy Mountain (University of New Mexico Press), Angle of Geese(David R. Godine), The Gourd Dancer (Harper and Row), The Names (Harper and Row), The Ancient Child(Doubleday), In the Presence of the Sun (St. Martin’s Press), The Man Made of Words (St. Martin’s Press), In the Bear’s House (St. Martin’s Press), Circle of Wonder: A Native American Christmas Story (University of New Mexico Press), Les Enfants du Soleil (Le Seuil, Paris), and Four Arrows and Magpie (Hawk Publ. Group). His play, The Indolent Boys, was given its world premiere at the Syracuse Stage in 1994, and his children’s play, Children of the Sun, opened at the Kennedy Center in 1997. Three Plays, which collects these plays, along with The Moon in Two Windows, was published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 2007. A book of photographs, The Storyteller’s Eye, reflecting his thirty years of travel in the former Soviet Union as well as his work with indigenous peoples around the world, is also forthcoming. A new collection of poetry, a new children’s book, and a memoir are in progress.

Momaday has been a commentator of National Public Radio, the voice of the National Museum of the American Indian of the Smithsonian Institution, the narrator of PBS documentaries including “Remembered Earth” and “Last Stand at Little Bighorn,” and he was a featured on-camera commentator on the PBS series “The West”, produced by Ken Burns and directed by Stephen Ives. He has lectured and given readings in many countries of the world. He presided over and was the keynote speaker for UNESCO’s International Symposium on Indigenous Identities in 2001, and participated in Brainstorm 2001, 2002, and 2003, the Fortune Editors’ Invitational (Fortune Magazine and the Aspen Institute). His essays and articles have appeared in Natural History, American West, The New York Review of Books, New York Newsday, The New York Times, and other periodicals, and most recently in Lewis and Clark Through Native Eyes (Knopf, Alvin Josephy, ed.). His introduction to The Way to Rainy Mountain is included in The Best American Essays of the Century (Houghton Mifflin, 2000, Joyce Carol Oates and Robert Atwan, eds.).

His paintings, drawings and prints have been exhibited in the US and abroad. A one-man, 20-year retrospective was mounted at the Wheelwright Museum, Santa Fe in 1992-1993. Most recently Jacobson House at the University of Oklahoma presented a retrospective of his work and selections from his parents’ work in May 2006

Momaday was a founding trustee of the National Museum of the American Indian and is a founding member of the Stewardship Council of the Autry Center for the American West. He is the founder and chairman of The Buffalo Trust, a non-profit foundation for the preservation and restoration of indigenous culture and heritage, with projects in the American Southwest, Oklahoma, Alaska, and Siberia. He has been actively involved in partnership projects with indigenous peoples in Siberia since his Fulbright professorship in 1974, and with UNESCO in the United States, Europe and Siberia since 2003. He also is the founder of the nonprofit Rainy Mountain Foundation in Oklahoma, which is building an archive and camp for Native American youth at Rainy Mountain, Oklahoma.

On July 12, 2007, the State of Oklahoma named Momaday the Centennial Poet Laureate, a position in which he traveled and met with people throughout the state to celebrate poetry and Native American oral traditions. He holds the honor of Poet Laureate in the Kiowa tribe, and he is the New Mexico Centennial Distinguished Writer. In the current year (2014) Momaday is Adjunct Professor of Native American studies at the Institute of American Indian Arts and Artist in Residence at St. John’s College, Santa Fe.