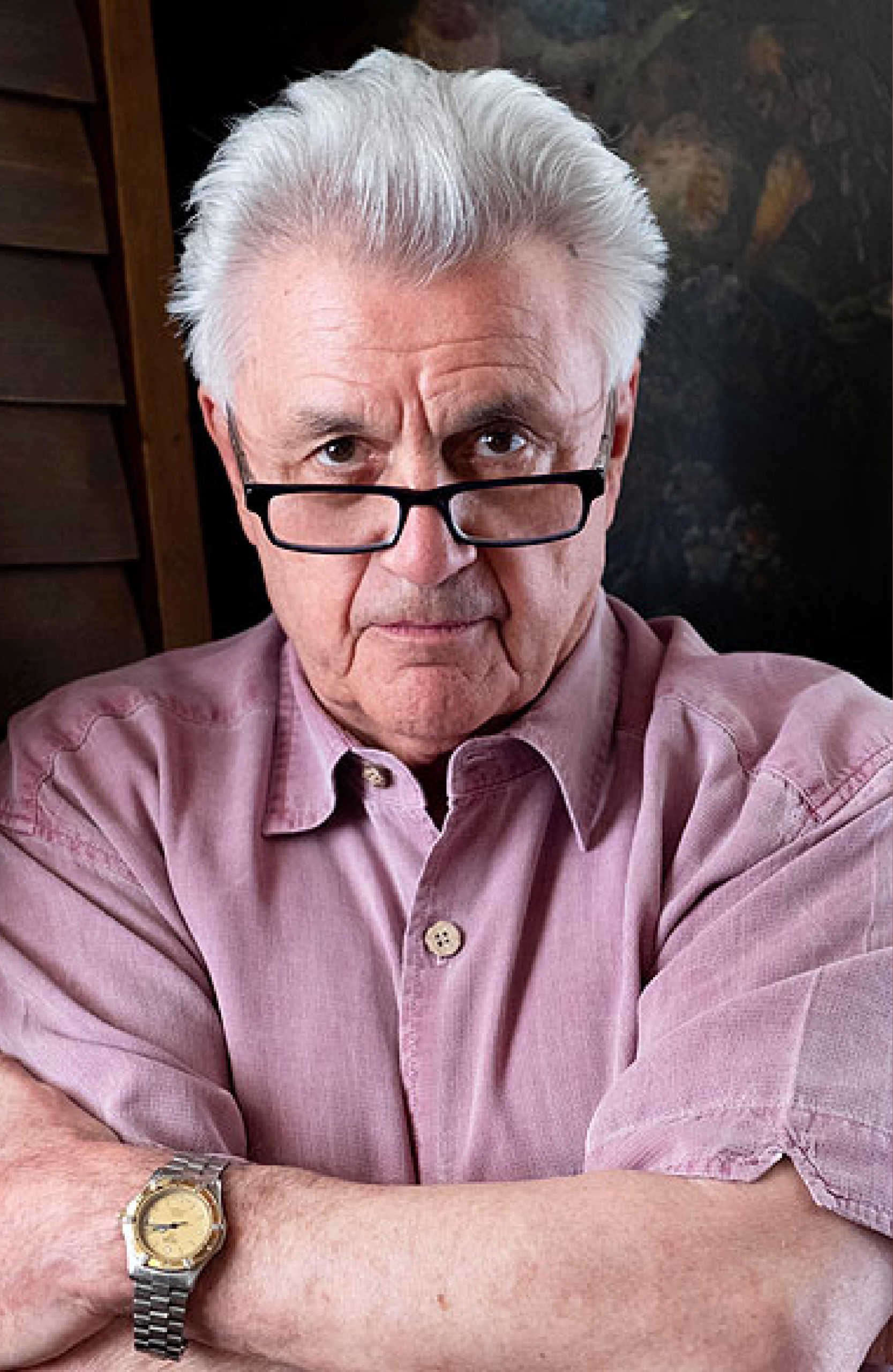

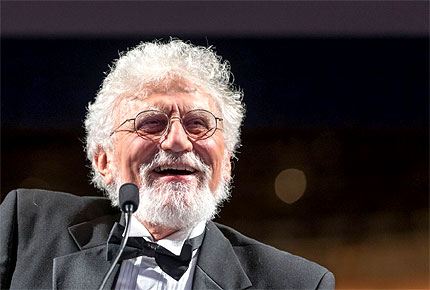

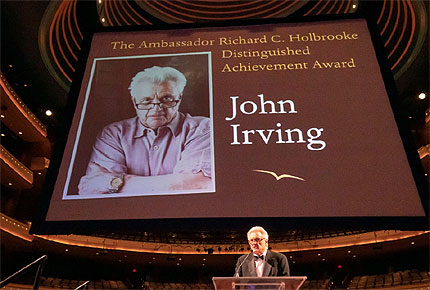

Over the past 50 years, no American literary lion has roared as mightily across the planet as the novelist John Irving, the indefatigable author of fourteen novels, ten of which have been international bestsellers.

The 76-year-old Irving has been widely celebrated, both here and abroad, as a master storyteller and comic genius, and praised resoundingly for his intrepid and fearless engagement with controversial subject matter, and for the depth of his empathetic humanity, both as an artist and as a person. Translated into more than 35 languages, Irving’s narcotically-addictive fictions have made him a household name in dozens of nations, and earned him the rare status of an acclaimed literary writer who has simultaneously achieved stratospheric popular commercial success. It can also be said with some certainty that John Irving is the only Literary Lion in history to be both inducted into the Wrestling Hall of Fame and presented with an Oscar for screenwriting.

Born in 1942 in Exeter, New Hampshire, Irving’s early wanderlust landed him in Vienna, Austria, at age 21, a decision which prevented Irving from ever being pigeon-holed as a Yankee regionalist. Beginning in 1968 with Setting Free The Bears, published a year after Irving had earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop, Austria played a pivotal role is his first five novels. Although New England would serve as the focus of many of the author’s narratives, in later work as well Irving proved to be an enthusiastic globe-trotter, always expanding the playing field for his art and enhancing his universal appeal.

Irving, a famous contrarian, claims to disdain the label “Great American Novel,” and guffaws at any suggestion that such a thing might exist, yet he himself has written three works critically considered to be worthy of just such an appraisal.

The World According To Garp (1979) received a National Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Garp was not only a publishing blockbuster but a cultural phenomenon that skyrocketed Irving to a zone of celebrityhood never experienced by most authors. What enthralled audiences and critics alike, besides a riveting story-line, were Irving’s fascinating community of characters, who made the exotic (transgenderism, dwarfism) familiar, and the familiar uncomfortably and often tragically flawed. It was in Garp that Irving’s artistic prescience had a powerful impact on our culture, and all cultures. One could read Irving to get a sense of what the future would bring us–in 1979, his understanding that sexuality and its various evolutions, blendings and blurrings would become a central social, moral and political issue of our time, and a stage upon which all open-hearted people would struggle for social justice.

Again, in The Cider House Rules (1985), Irving’s audiences would not escape one of our nation’s most volatile political and theological conflicts–abortion, and a woman’s right to her own body. The thematic stakes at the core of Cider Houseencircled readers with the fog of paralyzing ambiguities that bedevil human existence, the clash of profound truths that bewilder us with cosmic irony.

Audiences worldwide would vote A Prayer for Owen Meany to the top of the list of Irving’s work as a true American classic. All the trademark Irving themes are radioactively present here from the minute a young boy hits a baseball into the stands and kills his best friend’s mother–random violence, absent parents, the nature of families and friendship, the dynamo of sexuality, the UnderToad–in this case the Vietnam War–lurking in the background to swallow our dreams. Here, too, we discover Irving’s passion for exploring the complexities of religion and Christianity, not a territory where many writers dare to venture.

John Irving wants to be known as a world-class entertainer, and he is. He also wouldn’t mind if we think of him as our own generation’s version of Charles Dickens, and we do. But what makes Irving such a beloved author around the world is that, against the violence he finds sweeping down on us, he provides the counterweight of gentle affection between people, merciful and sincere and indeed heart-breaking in its frequent futility. And against desperation and bigotry and hatred, we find in Irving, always when we least expect it, a brave hand, extended. When all the accounting is done, he will be remembered as one of the most generous writers of the human spirit.

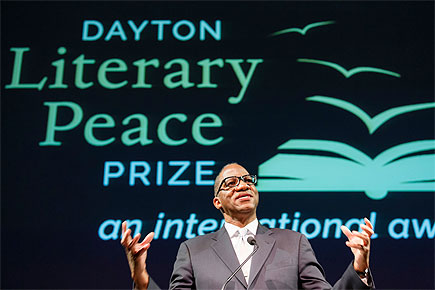

Bob Shacochis

author of The Woman Who Lost Her Soul

2014 Recipient of the Dayton Literary Peace Award for Fiction