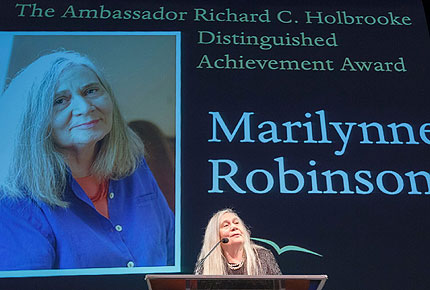

Marilynne Robinson is the author of four exquisite novels and five nonfiction works collecting lectures and essays previously published in such eminent journals of ideas as

The New York Review of Books, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Nation, Harper’s, and

The Christian Century. The essays are earnest, learned, knotted, and closely reasoned, springing from Robinson’s deeply considered, radically democratic Calvinism. They read like a cross between humanist homiletics and sharp cultural criticism. To read them is to feel the author’s mind wrestling with the big questions — Grace, Fear, Being — as Jacob wrestled with the angel.

The novels, like most of the essays, have one-word titles —

Housekeeping, Gilead, Home, and

Lila — as though they too name the questions they will take up. But these questions have a more human scale than those of the essays and, as befits novels, pose the questions in terms of personal relationships. Her characters traverse the vast interpersonal spaces between belonging and alienation, most without ever leaving town. Each novel follows a small group of people, the last three centering on essentially the same community of people living in mid-twentieth-century middle-America, and the action is for the most part small: a prodigal returns; an elderly dying man contemplates his life and writes a letter to his son; a homeless young woman finds a home; a young woman leaves home and finds her true family. But the issues are big: the wages of America’s original sin of slavery; the care and keeping of the environment; the debt owed our children and their children; the burdens and blessings of reconciliation.

On one level Robinson’s fiction itemizes homely local virtues, the sort we have in mind when we speak nostalgically of small-town America or imagine a more innocent, happier past time. But on another level Robinson invites us to contemplate how a virtuous patina permits us to mask our darker selves. Thus the good people of Gilead, the setting for her most recent three novels, hearken back to their town’s abolitionist past but in their present engage in or simply accept the sort of petty acts of passive and not-so-passive racism and sexism that can drive a black or mixed-race family or a single mother from their town. Kindness to neighbors is as good a thing in Robinson’s fictional world as it is on the road to Jericho or on the journey of life. But, she reminds us, only when we grasp the difficult concept that “neighbor” describes all our fellow travelers do we even begin to approach the ideal Good. The novels offer both rebuke and counsel, without being didactic: they are, in fact, full of sensuous pleasures in characterization, description, mood, and voice.

Late in 2015, Marilynne Robinson sat down for a lengthy chat with one of her biggest fans, President Barack Obama. Published in two parts in

The New York Review of Books, the conversation ranged far and wide, but touched again and again on a deceptively simple shared principle. As Robinson put it, “the basis of democracy is the willingness to assume well about other people. You have to assume that basically people want to do the right thing.” Graceful and accomplished, ethical and humane, Robinson’s writing has for over thirty years reminded, encouraged, pushed, and sometimes prodded readers to do that right thing and, in the process, to become reacquainted with what another U.S. President (who would surely also have admired her work) called “the better angels of our nature.”

—Carol S. Loranger

Chair, Department of English Language and literatures

College of Liberal Arts

Faculty President

Wright State University