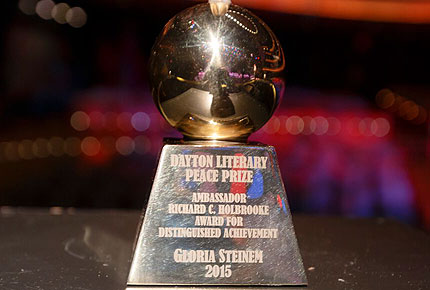

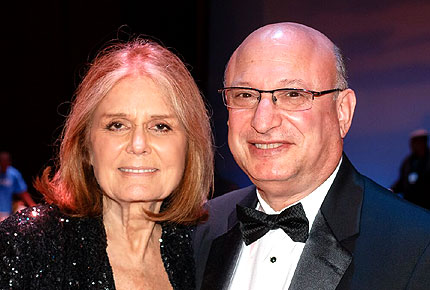

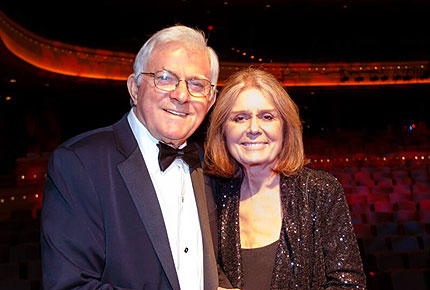

By means of the Richard C. Holbrooke Distinguished Achievement Award, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize Foundation proudly honors Gloria Steinem: writer, feminist icon, peace activist, political organizer, and visionary guide. Steinem became a household name in the 1970s as a founder of, fighter for, and frequent contributor to

Ms. magazine. Four decades later, she continues to be a vaunted leader of and spokesperson for worldwide feminism. Gloria Steinem once credited Simone de Beauvoir with inspiring the women’s movement; many today believe Steinem deserves credit for much of what feminism has accomplished since. From the 1960s onward, she has been the single strongest voice speaking for and to women (and the many listening men) during what has been called the world’s “longest revolution.”

Peace has always been crucial to Steinem’s feminism and to her efforts to aid other causes: the civil rights movement, fair treatment of farm workers, and the end of conflict in Vietnam. An Ohio native, she graduated from Smith College, and then traveled to India where she became a student of Mohandas Gandhi’s ideas about nonviolence. These, she learned, grew in part out of India’s women’s movement preceding him. After coursework at the University of Delhi, Steinem participated in nonviolent protests of the caste system in southern India. During demonstrations, she came face to face with the deplorable treatment of underclass women in India, an experience that led her to see parallels in equally dismal conditions for women in other parts of the world.

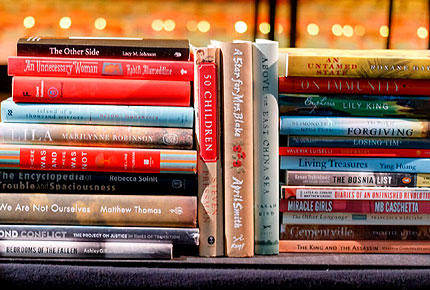

Steinem’s career has been all about words leading to peaceful political action, much of it in behalf of women. Through books, essays, speeches, panel presentations, interviews, and conversations and through marshaling the ideas of other feminists into publication, she has defined the women’s movement and created untold improvements in women’s and men’s lives. Her

Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983) contains her early, insightful essays on feminism. They continue to resonate with readers, even after thirty years. vRevolution from Within: A Book of Self-Esteem (1992) is based on the premise that not only are there “external barriers to women’s equality,” but also there are “internal ones, too,” emotional damages often done by patriarchy, that sufferers themselves must heal; in

Doing Sixty and Seventy (2006) Steinem explains why women tend to become radicalized feminists as they age. Nor has Steinem herself mellowed with time. She continues speaking out about the economic preference in some places for sons over daughters, female genital mutilation, enforced child marriage, sex trafficking, sex-tourism, domestic violence, honor killings, and dowry deaths. Sadly, the list goes on and on. Due out in October is Steinem’s

My Life on the Road that connects travel with activism. One doesn’t journey far without seeing how much work in gender equality remains to be done.

In her writing and speeches, Steinem has shown the relationship between equal rights for all and peace on planet Earth. Like the authors of seminal study

Sex and World Peace (2012), Steinem teaches that nations treating women badly are often poor, that countries promoting gender equality are less likely to go to war and are less likely to be the first to inflict damage. Repeatedly, Steinem has asserted that gender inequality is related to security issues on both national and international levels, that efforts to achieve peace in the world need also address “the violence and exploitation that occur in personal relationships between the two halves of humanity, men and women” (5). As have the authors of

Sex and World Peace, Steinem has been on the forefront in pointing out that, for there to be peace on

any level, females must, first, be physically safe in their homes and towns with the power to make decisions in regard to their own bodies. Second, laws must protect females in the same ways they protect males, and third, women must participate equally in “the councils of human decision making at all levels” (6). Silenced women’s voices have been

a, if not

the, key cause of international discord. Gender equality, Steinem would say, is a

precondition for world peace, a goal she has spent her life working toward.

It was Gloria Steinem who long ago famously quipped, “A woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle.” True as her observation was for its own time, she might now say, “Forget the bike: worldwide, women and men simply

must interact equally and peaceably with each other; further, we have to do a better job of protecting fish if we are all to survive.

– Mary Beth Pringle

Emerita Professor of English

Wright State University