Play Video

“I am excited to have the prize–especially when I see the books that were nominated along with mine. It is heartening to be judged worthy of that company, and to be singled out among them is deeply humbling.”

— Richard Bausch

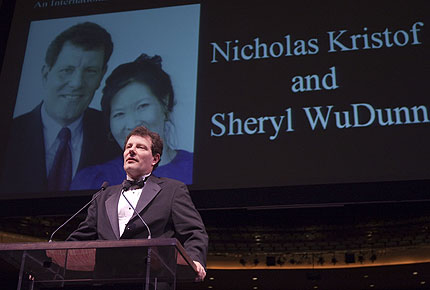

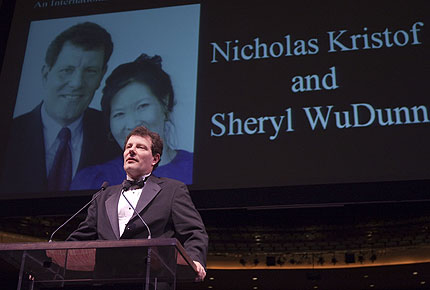

“The challenge is to approach issues by carrying passion while acknowledging that your views carry with them a certain cultural burden, that you may well be wrong, that your views are tentative, and yet not being afraid to make moral judgments; acknowledging you perhaps are wrong, but yet to act. It’s a difficult terrain to maneuver, a complicated one that can contain inconsistencies, but it also reflects the complicated world out there.”

— Nicholas Kristof who with his wife Sheryl WuDunn received the 2009 Dayton Literary Peace Prize Lifetime Achievement Award

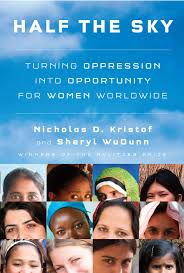

In recognition of their work chronicling human rights in Asia, Africa, and the developing world, authors and journalists Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn will receive the 2009 Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Lifetime Achievement.

Since becoming the first married couple to win a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of the Tiananmen Square protests for the New York Times, Kristof and WuDunn have collaborated on such influential, milestone books as China Wakes: The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power and Thunder from the East: Portrait of a Rising Asia. In 2006, Kristof received a second Pulitzer Prize for his New York Times op-ed columns on Darfur. Their latest book, Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, was released in September 2009.

The waiting was changing him, emptying him, draining all the human elements, as if his spirit were bleeding. He tried to picture Helen, his father and mother, the street, the surround, as he had seen it on that last day. He could not call it up. He could not begin to imagine it. The memory of it all was breaking up, dissolving, being effaced awfully. He could see quite clearly the eyes filled with wonder of the dying soldier, the woman’s smudged calves. He had become a pair of eyes, staring, two hands on a rifle. A cold watchfulness, shivering in the wind, waiting.

The waiting was changing him, emptying him, draining all the human elements, as if his spirit were bleeding. He tried to picture Helen, his father and mother, the street, the surround, as he had seen it on that last day. He could not call it up. He could not begin to imagine it. The memory of it all was breaking up, dissolving, being effaced awfully. He could see quite clearly the eyes filled with wonder of the dying soldier, the woman’s smudged calves. He had become a pair of eyes, staring, two hands on a rifle. A cold watchfulness, shivering in the wind, waiting.

The Women’s Crusade

Traditionally, the status of women was seen as a “soft” issue—worthy but marginal. We initially reflected that view ourselves in our work as journalists. We preferred to focus instead on the “serious” international issues, like trade disputes or arms proliferation. Our awakening came in China.

After we married in 1988, we moved to Beijing to be correspondents for The New York Times. Seven months later we found ourselves standing on the edge of Tiananmen Square watching troops fire their automatic weapons at prodemocracy protesters. The massacre claimed between 400 and 800 lives and transfixed the world; wrenching images of the killings appeared constantly on the front page and on television screens.

Yet the following year we came across an obscure but meticulous demographic study that outlined a human rights violation that had claimed tens of thousands more lives. This study found that 39,000 baby girls died annually in China because parents didn’t give them the same medical care and attention that boys received — and that was just in the first year of life. A result is that as many infant girls died unnecessarily every week in China as protesters died at Tiananmen Square. Those Chinese girls never received a column inch of news coverage, and we began to wonder if our journalistic priorities were skewed.

The waiting was changing him, emptying him, draining all the human elements, as if his spirit were bleeding. He tried to picture Helen, his father and mother, the street, the surround, as he had seen it on that last day. He could not call it up. He could not begin to imagine it. The memory of it all was breaking up, dissolving, being effaced awfully. He could see quite clearly the eyes filled with wonder of the dying soldier, the woman’s smudged calves. He had become a pair of eyes, staring, two hands on a rifle. A cold watchfulness, shivering in the wind, waiting.

The waiting was changing him, emptying him, draining all the human elements, as if his spirit were bleeding. He tried to picture Helen, his father and mother, the street, the surround, as he had seen it on that last day. He could not call it up. He could not begin to imagine it. The memory of it all was breaking up, dissolving, being effaced awfully. He could see quite clearly the eyes filled with wonder of the dying soldier, the woman’s smudged calves. He had become a pair of eyes, staring, two hands on a rifle. A cold watchfulness, shivering in the wind, waiting.

“I am excited to have the prize–especially when I see the books that were nominated along with mine. It is heartening to be judged worthy of that company, and to be singled out among them is deeply humbling.”

— Richard Bausch

Richard Bausch is the author of eleven novels. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, Playboy, GQ, Harper’s Magazine, and other publications and has been featured in numerous best-of collections, including The O. Henry Awards’ Best American Short Stories, and New Stories from the South.

He is chancellor of the Fellowship of Southern Writers and lives in Memphis, Tennessee, where he is Moss Chair of Excellence in the Writer’s Workshop of the University of Memphis.

Three hapless American soldiers, sent out on reconnaissance at the end of World War II, end up, more by mistake than design, scaling a mountain in a snowstorm. It is the brutal Italian winter of 1944. While the soldiers struggle to keep their bearings, the atrocities surrounding them — on both sides of the conflict — are too corrosive for such a sensitive instrument as a moral compass. Soon the three are lost — and not just physically.

Richard Bausch’s Peace is a spare, beautiful, breathlessly told drama. To read the novel is to enter a cold winter nightscape in which, contrary to the title, no peace may be found. The book concerns itself less with the big concepts of World War II — Allied, Axis, Nazism, Fascism — than with the minute physical depravation of men hunting one another across an icy landscape. Bausch’s mountain is partly mythic. A freezing rain continuously falls. Deer loom out of the dark like avatars from another, saner world. The ancient Italian farmer who guides the Americans may in fact be trying to kill them. A pivotal moment occurs near the short novel’s end, when one of the soldiers, Robert Marson, shows a singular act of private mercy amid the flood of public violence. Ordered to assassinate their Italian guide, who is revealed at last for a Fascist (and probably a spy), Marson disobeys his superior. He takes the old man into the woods, and sets him free.

“’Do your duty,’ his father had said.” writes Bausch, “And he could not find in his heart what the word meant anymore.” Marson, in the end, does not do his duty. He does the right thing. In the depth of his conscious, he finally finds a compass reading. The true north of compassion; it might just lead to a moment’s peace.

— Brad Kessler, 2009 finalist judge

2007 Fiction winner for Birds in Fall

The waiting was changing him, emptying him, draining all the human elements, as if his spirit were bleeding. He tried to picture Helen, his father and mother, the street, the surround, as he had seen it on that last day. He could not call it up. He could not begin to imagine it. The memory of it all was breaking up, dissolving, being effaced awfully. He could see quite clearly the eyes filled with wonder of the dying soldier, the woman’s smudged calves. He had become a pair of eyes, staring, two hands on a rifle. A cold watchfulness, shivering in the wind, waiting.

“I believe artists should be able to step into other people’s situations, contexts and cultures and work from there. If artists don’t have that freedom, then, as someone has said, are we all writing our autobiographies?”

— Uwen Akpan

Uwem Akpan was born in Ikot Akpan Eda in southern Nigeria. After studying philosophy and English at Creighton and Gonzaga universities, he studied theology for three years at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa. He was ordained as a Jesuit priest in 2003 and received his MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan in 2006.

“My Parents’ Bedroom,” a story from his short story collection, Say You’re One of Them, was one of five short stories by African writers chosen as finalists for The Caine Prize for African Writing 2007. Say You’re One of Them won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book (Africa Region) 2009 and PEN/Beyond Margins Award 2009, and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction.

In 2007, Akpan taught at a Jesuit college in Harare, Zimbabwe. Now he serves at Christ the King Church, Ilasamaja-Lagos, Nigeria.

We laughed at the gangs of street kids massed together in sound sleep. Some gangs slept in graded symmetry. Others slept freestyle. Some had a huge tarp above their piles to protect them from the elements. Others had nothing. We laughed at a group of city taxi drivers huddled together, warming themselves with cups of Chai and firey political banter while waiting for the Akamba buses to arrive with passengers from Tanzania and Uganda. Occasionally we’d see the anxious faces of these visitors in the old taxis, bracing for what would be the most dangerous twenty minutes of their twelve hour journeys, fearful of being robbed whenever the taxis slowed down.

We laughed at the gangs of street kids massed together in sound sleep. Some gangs slept in graded symmetry. Others slept freestyle. Some had a huge tarp above their piles to protect them from the elements. Others had nothing. We laughed at a group of city taxi drivers huddled together, warming themselves with cups of Chai and firey political banter while waiting for the Akamba buses to arrive with passengers from Tanzania and Uganda. Occasionally we’d see the anxious faces of these visitors in the old taxis, bracing for what would be the most dangerous twenty minutes of their twelve hour journeys, fearful of being robbed whenever the taxis slowed down.

It is impossible to emerge unchanged after reading the five astonishing, harrowing, desperately beautiful stories in Uwem Akpan’s Say You’re One of Them, a collection centered upon children in various African countries. The book is increasingly garnering acclaim because it does what the best literature has always done: It invites us into a realm that may be new to us, and at the same time it illuminates the world to which all of us inescapably belong. The title itself carries a dual meaning: The mother in “My Parents’ Bedroom” counsels her daughter to pretend to belong to the tribe that wishes her harm. But “saying you’re one of them” also carries a moral imperative, one that courses in the veins of these brilliantly alive stories: We must recognize and declare our human links with every body and soul on earth, every conflict, every suffering child.

Though large subjects are tackled — human trafficking, starvation, tribal massacres — the book is never didactic, never preachy, never too generalized; instead, the writing reminds us of the tremendous ability of fiction to haunt, to get under our skin and into our heart as well as into our mind. The finely-wrought images are so intense that they turn into imprints that a reader will carry forever: A twelve-year-old prostitute staggers home with money to help her brother gain an education; parents urge their children to sniff glue to stave off hunger; meat must be eaten carefully in order to avoid biting into the “pellets that had brought down the animal”; motorcycles are blessed in a church where wealth is hailed as the approach to God. No reader will close the book after the closing scene in the last story — one of five finalists for the Caine Prize for African writing — without being knocked sideways with what has to be one of the most shocking, breathlessly powerful moments to grace a written page in any language and in any time.

Children guide us through realms where the adults entrusted with their care cannot be trusted. In “Fattening for Gabon,” we are trapped in a dark, airless room with ten-year-old Kotchikpa and his five-year-old sister, Yewa. When he cannot persuade her to race through a window to escape being sold into slavery by their family, he hurtles forward alone and declares, “I ran into the bush, blades of elephant grass slashing my body, thorns and rough earth piercing my feet … I ran and I ran, though I knew I would never outrun my sister’s wailing.” In “Luxurious Hearses,” unclaimed dead bodies are crammed inside buses doomed to wander like ships without a port, and the eyes of our narrator, Jubril, “…were tired and so sunk in, it seemed tears would never climb their steep banks to be shed.” But the collection is also rich with gentle, humane incident: A mother takes a gift of dried milk “carefully in her hands, like one receiving a diploma” and in peaceful times, kites are flown joyfully, “rising against the distant coffee fields,” and friends adore calling out rhymes from opposing balconies. Schoolchildren see words as hallowed, full of the hope of salvation.

The writing is clear-sighted but poetic; it’s unflinching but, in the end, etched fully with a sense of delicacy and redemption. Depicted here so vividly is a continent in utter upheaval. Children are without homes; the social fabric is so torn that families are caught up in betraying one another. The lingering effect of this spectacular work of art is that readers will also find themselves incapable of outrunning the howling but also the grace at its core. Rarely does one read a book that hits so forcefully, and with such devastating and loving accuracy, with the sense that a continent unmoored means that we, too, are unsettled.

— Katherine Vaz

2009 finalist judge

It is impossible to emerge unchanged after reading the five astonishing, harrowing, desperately beautiful stories in Uwem Akpan’s Say You’re One of Them, a collection centered upon children in various African countries. The book is increasingly garnering acclaim because it does what the best literature has always done: It invites us into a realm that may be new to us, and at the same time it illuminates the world to which all of us inescapably belong. The title itself carries a dual meaning: The mother in “My Parents’ Bedroom” counsels her daughter to pretend to belong to the tribe that wishes her harm. But “saying you’re one of them” also carries a moral imperative, one that courses in the veins of these brilliantly alive stories: We must recognize and declare our human links with every body and soul on earth, every conflict, every suffering child.

Though large subjects are tackled — human trafficking, starvation, tribal massacres — the book is never didactic, never preachy, never too generalized; instead, the writing reminds us of the tremendous ability of fiction to haunt, to get under our skin and into our heart as well as into our mind. The finely-wrought images are so intense that they turn into imprints that a reader will carry forever: A twelve-year-old prostitute staggers home with money to help her brother gain an education; parents urge their children to sniff glue to stave off hunger; meat must be eaten carefully in order to avoid biting into the “pellets that had brought down the animal”; motorcycles are blessed in a church where wealth is hailed as the approach to God. No reader will close the book after the closing scene in the last story — one of five finalists for the Caine Prize for African writing — without being knocked sideways with what has to be one of the most shocking, breathlessly powerful moments to grace a written page in any language and in any time.

Children guide us through realms where the adults entrusted with their care cannot be trusted. In “Fattening for Gabon,” we are trapped in a dark, airless room with ten-year-old Kotchikpa and his five-year-old sister, Yewa. When he cannot persuade her to race through a window to escape being sold into slavery by their family, he hurtles forward alone and declares, “I ran into the bush, blades of elephant grass slashing my body, thorns and rough earth piercing my feet … I ran and I ran, though I knew I would never outrun my sister’s wailing.” In “Luxurious Hearses,” unclaimed dead bodies are crammed inside buses doomed to wander like ships without a port, and the eyes of our narrator, Jubril, “…were tired and so sunk in, it seemed tears would never climb their steep banks to be shed.” But the collection is also rich with gentle, humane incident: A mother takes a gift of dried milk “carefully in her hands, like one receiving a diploma” and in peaceful times, kites are flown joyfully, “rising against the distant coffee fields,” and friends adore calling out rhymes from opposing balconies. Schoolchildren see words as hallowed, full of the hope of salvation.

The writing is clear-sighted but poetic; it’s unflinching but, in the end, etched fully with a sense of delicacy and redemption. Depicted here so vividly is a continent in utter upheaval. Children are without homes; the social fabric is so torn that families are caught up in betraying one another. The lingering effect of this spectacular work of art is that readers will also find themselves incapable of outrunning the howling but also the grace at its core. Rarely does one read a book that hits so forcefully, and with such devastating and loving accuracy, with the sense that a continent unmoored means that we, too, are unsettled.

— Katherine Vaz

2009 finalist judge

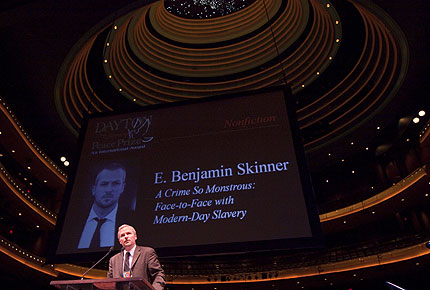

“By highlighting modern-day slavery and the fight for its abolition, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize committee pushed forward the “unfinished work” that President Lincoln spoke about that Thursday afternoon in Gettysburg. There are more slaves today than at any point in human history, and I’m deeply honored, and humbled, to be recognized by the committee as being among those working for their freedom.”

— Benjamin Skinner

[A first-time author, Skinner is donating his $10,000 honorarium to Free The Slaves, the American wing of Anti-Slavery International, the world’s oldest human rights organization.]

Born in 1976, Ben Skinner was raised in Wisconsin and northern Nigeria, where his father had served as a British colonial administrator. He first learned about slavery as a child in Quaker meeting. The Quakers, who believed that the divine spark animates every man, were the first abolitionists. Skinner’s Sunday school teachers spent as much time on Harriet Tubman and William Lloyd Garrison as they did on Moses and Jesus.

Skinner himself comes from abolitionist stock. His great-great-grandfather, Robert Pratt, served with the 1st Connecticut Artillery at the Siege of Petersburg, the ten-month campaign which bled white the Confederate Army and led to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Pratt’s uncle was a comb-maker too old to serve at the time, but not too old to make fiery antislavery speeches. When one of his distributors told him his abolitionist talk was hurting sales in the south, he exploded: “If they won’t buy my Yankee combs, then let them go lousy!”

In 2003, as a writer on assignment in Sudan for Newsweek International, Skinner met his first survivor of slavery. He had first flown in under enemy radar with an Evangelical group purporting to buy slaves en masse to secure their freedom. Afterwards, on his own, he hitched a ride on a U.N. Cessna to the frontlines of the north-south Sudanese civil war. There he met Muong Nyong. Like Skinner, Nyong was 27 at the time, and pondering what to do with the rest of his life. Unlike Skinner, he had spent the first part of that life in bondage.

After meeting Nyong, Skinner traveled the globe to find others like him. Scholars estimate the total number of modern-day slaves is greater than at any point in history. But the number means nothing, unless slavery means something. Skinner adopted a narrow definition: slaves are forced to work, under threat of violence, for no pay beyond subsistence.

Though there are more slaves today than ever before, finding them would prove the most daunting challenge of Skinner’s professional life. Slaves languish in shadows, kept hidden by violent traffickers and masters. Going undercover when necessary, Skinner infiltrated trafficking networks and slave quarries, urban child markets and illegal brothels. In the process, he became the first person in history to observe the sales of human beings on four continents.

A graduate of Wesleyan University, Skinner is currently a fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government and previously served as a Research Associate for U.S. Foreign Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations as well as Special Assistant to Ambassador Richard Holbrooke. As a writer engaged in the study of the U.S. and global political economies, his articles have appeared in Newsweek International, Travel + Leisure, Los Angeles Times, The Miami Herald, Foreign Policy and others. He lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Most Americans think that slavery ended in the United States in either 1862 with the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effective in 1863 or in 1865 when the 13th amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified. That the civilized world, either before and not very long after the American Civil War, also ended slavery. Skinner’s extraordinary book reminds us the one of the oldest and most brutal institutions in human history—the utter subjection of one human being to another without compensation of any sort, without legal protection of any kind, and without escape except, against great odds, by risking one’s life–is alive and well around the world, even in the United States, albeit underground, beneath the notice of the average citizen. And few politicians in the world are doing much of anything about it.

If nothing else, Skinner reminds the reader of what the word “slavery” really means, as it is so commonly used “as a metaphor for underpaid and over-worked wage laborers.” The people in Skinner’s tale work simply to stay alive; wage slavery is a contradiction in terms. There are no people here who are, to borrow the title of William Rhoden’s book about black American athletes, “Forty Million Dollar Slaves.” After reading this book, no one will use the word “slavery” metaphorically again. There is, Skinner makes clear, nothing like slavery but slavery.

Skinner’s eye-opening investigative report is something of a perverse travelogue; from Haiti to Romania, from Sudan to northern India, Skinner takes us to various hell-holes of the sex trade, tribal warfare, child labor, and grinding, inhuman poverty to reveal the incredible network of slavery, mostly women and children, beaten, raped, starved, worked to exhaustion and beyond, sold from one buyer to another in a thriving subculture of nightmarish commerce, a demented Spencerian fable of savage predators devouring the weak; all of which is frequently supported by the dollars of middle-class and wealthy western and Asian tourists. A highly readable, though at times stomach-churning book, graphically describing beatings, rapes, prostitution, and child abuse, Skinner’s words seems alit with the moral fire of the old-time muckrakers like Steffens, Riis, and Tarbell. “It takes all of us,” Skinner pleads at the end of his book, in his call to fight against slavery, “The original abolitionists were a varied lot, and their successes were due in part to their varied battle plans. From John Brown’s carbines and pikes to Charles Sumner’s verbs and nouns, the antislavery vanguard used widely differing tools, but united in a common cause. Now, as then, all personalities are welcome.”

The woman who had employed her mother took in the girl as a restavek, a child slave. Without her mother, Little Hope’s life was loveless. But her lot was better than that of many of restaveks, as her mistress fed her regularly and, in keeping with a promise to (her mother) sent her to school. Still, domestic duties impeded her schoolwork. The house, with two stories and a dozen rooms, was a lot for the young girls to clean, and without automated appliances, she had to wash the dishes, clothes and diapers by hand.

One day in 1996, Marie Pompee, sister of the mistress, came to visit. An American citizen, Marie was the breadwinner for relatives back on the island, visiting frequently and bringing clothes and money from her home in Miami. She was normally well dressed, favoring gold jewelry and pantsuits, well fed and well coiffed. To Little Hope, she – and America – meant comfort and luxury.

Mary now told the nine-year old that she would send for her. For the first time since her mother died, the girl felt hope. Perhaps sensing her optimism, Marie quickly put the girl in her place.

“If I bring you to America,” Marie told her, “you will be my slave.”

There is clearly in the book the great moral energy of the great American abolitionists like Theodore Weld, Theodore Parker, and William Lloyd Garrison. It does not offer merely a description or account of a problem but the cry for action. Early on, Skinner formulates his own anti-slavery ethic: “I couldn’t overcome my instinct that no matter how just the cause, a human life should not be bought—even if it means that someone else may buy it instead. I established a principle for the rest of my work: I would give no money to slave masters.” But even at its darkest, there is a great sense of uplift in this book, no just from the story of anti-slavery Bush administration official John Miller, but from some of the slaves themselves, like Tatiana and Bill Nathan, who escaped their terrible situations and fought back against the evil. There are moments of heroism here, a parent seeking a lost child or a parent giving up her life for her child, that reminds one of there is a sense of triumph even in the worst, most despairing human defeats. Skinner reminds us how much some of us will fight to remind the world that we are human, not things to be used or exploited, not extensions of someone else’s will. For relating this with both honesty and compassion, Skinner deserves the highest praise and the deepest appreciation.

– Gerald Early, 2009 finalist judge

Washington University in St. Louis

Most Americans think that slavery ended in the United States in either 1862 with the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effective in 1863 or in 1865 when the 13th amendment, abolishing slavery, was ratified. That the civilized world, either before and not very long after the American Civil War, also ended slavery. Skinner’s extraordinary book reminds us the one of the oldest and most brutal institutions in human history—the utter subjection of one human being to another without compensation of any sort, without legal protection of any kind, and without escape except, against great odds, by risking one’s life–is alive and well around the world, even in the United States, albeit underground, beneath the notice of the average citizen. And few politicians in the world are doing much of anything about it.

If nothing else, Skinner reminds the reader of what the word “slavery” really means, as it is so commonly used “as a metaphor for underpaid and over-worked wage laborers.” The people in Skinner’s tale work simply to stay alive; wage slavery is a contradiction in terms. There are no people here who are, to borrow the title of William Rhoden’s book about black American athletes, “Forty Million Dollar Slaves.” After reading this book, no one will use the word “slavery” metaphorically again. There is, Skinner makes clear, nothing like slavery but slavery.

Skinner’s eye-opening investigative report is something of a perverse travelogue; from Haiti to Romania, from Sudan to northern India, Skinner takes us to various hell-holes of the sex trade, tribal warfare, child labor, and grinding, inhuman poverty to reveal the incredible network of slavery, mostly women and children, beaten, raped, starved, worked to exhaustion and beyond, sold from one buyer to another in a thriving subculture of nightmarish commerce, a demented Spencerian fable of savage predators devouring the weak; all of which is frequently supported by the dollars of middle-class and wealthy western and Asian tourists. A highly readable, though at times stomach-churning book, graphically describing beatings, rapes, prostitution, and child abuse, Skinner’s words seems alit with the moral fire of the old-time muckrakers like Steffens, Riis, and Tarbell. “It takes all of us,” Skinner pleads at the end of his book, in his call to fight against slavery, “The original abolitionists were a varied lot, and their successes were due in part to their varied battle plans. From John Brown’s carbines and pikes to Charles Sumner’s verbs and nouns, the antislavery vanguard used widely differing tools, but united in a common cause. Now, as then, all personalities are welcome.”

There is clearly in the book the great moral energy of the great American abolitionists like Theodore Weld, Theodore Parker, and William Lloyd Garrison. It does not offer merely a description or account of a problem but the cry for action. Early on, Skinner formulates his own anti-slavery ethic: “I couldn’t overcome my instinct that no matter how just the cause, a human life should not be bought—even if it means that someone else may buy it instead. I established a principle for the rest of my work: I would give no money to slave masters.” But even at its darkest, there is a great sense of uplift in this book, no just from the story of anti-slavery Bush administration official John Miller, but from some of the slaves themselves, like Tatiana and Bill Nathan, who escaped their terrible situations and fought back against the evil. There are moments of heroism here, a parent seeking a lost child or a parent giving up her life for her child, that reminds one of there is a sense of triumph even in the worst, most despairing human defeats. Skinner reminds us how much some of us will fight to remind the world that we are human, not things to be used or exploited, not extensions of someone else’s will. For relating this with both honesty and compassion, Skinner deserves the highest praise and the deepest appreciation.

– Gerald Early, 2009 finalist judge

Washington University in St. Louis

The woman who had employed her mother took in the girl as a restavek, a child slave. Without her mother, Little Hope’s life was loveless. But her lot was better than that of many of restaveks, as her mistress fed her regularly and, in keeping with a promise to (her mother) sent her to school. Still, domestic duties impeded her schoolwork. The house, with two stories and a dozen rooms, was a lot for the young girls to clean, and without automated appliances, she had to wash the dishes, clothes and diapers by hand.

One day in 1996, Marie Pompee, sister of the mistress, came to visit. An American citizen, Marie was the breadwinner for relatives back on the island, visiting frequently and bringing clothes and money from her home in Miami. She was normally well dressed, favoring gold jewelry and pantsuits, well fed and well coiffed. To Little Hope, she – and America – meant comfort and luxury.

Mary now told the nine-year old that she would send for her. For the first time since her mother died, the girl felt hope. Perhaps sensing her optimism, Marie quickly put the girl in her place.

“If I bring you to America,” Marie told her, “you will be my slave.”

— Thomas Friedman

Thomas L. Friedman, a world-renowned author and journalist, joined The New York Times in 1981 as a financial reporter specializing in OPEC- and oil-related news and later served as the chief diplomatic, chief White House, and international economics correspondents.

A three-time Pulitzer Prize winner, he has traveled hundreds of thousands of miles reporting the Middle East conflict, the end of the cold war, U.S. domestic politics and foreign policy, international economics, and the worldwide impact of the terrorist threat. His foreign affairs column, which appears twice a week in the Times, is syndicated to seven hundred other newspapers worldwide.

Friedman is the author of From Beirut to Jerusalem (FSG, 1989), which won both the National Book Award and the Overseas Press Club Award in 1989 and was on the New York Times bestseller list for nearly twelve months. From Beirut to Jerusalem has been published in more than twenty-seven languages, including Chinese and Japanese, and is now used as a basic textbook on the Middle East in many high schools and universities.

Friedman also wrote The Lexus and the Olive Tree (FSG, 1999), one of the best selling business books in 1999, and the winner of the 2000 Overseas Press Club Award for best nonfiction book on foreign policy. It is now available in twenty languages. Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11, issued by FSG in 2002, consists of columns Friedman published about September 11 as well as a diary of his private experiences and reflections during his reporting on the post-September world as he traveled from Afghanistan to Israel to Europe to Indonesia to Saudi Arabia.

In 2005, The World Is Flat was given the first Financial Times and Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award, and Friedman was named one of America’s Best Leaders by U.S. News & World Report.

Friedman graduated summa cum laude from Brandeis University with a degree in Mediterranean studies and received a master’s degree in modern Middle East studies from Oxford. He has served as a visiting professor at Harvard University and has been awarded honorary degrees from several U.S. universities. He lives in Bethesda, Maryland, with his wife, Ann, and their two daughters.

Can citizens be helped to understand the fundamental workings of the world? Thomas Jefferson was not optimistic — though he knew that the American experiment depended on it. “Convinced that the people are the only safe depositories of their own liberty,” he wrote, “and that they are not safe unless enlightened to a certain degree, I have looked on our present state of liberty as a short-lived possession unless the mass of the people could be informed to a certain degree.” The record since Jefferson composed those words, in 1805, has been decidedly mixed. And in the 21st century, the question of whether Americans can be “informed to a certain degree”—about the environment, about the world economy, about constitutional principles, about the judicious use of national power—before it is too late remains an open one.

No journalist has been more assiduous in attempting to explain the world — not just to Americans, but to people everywhere — than Thomas Friedman of The New York Times. His book The Lexus and the Olive Tree (1999) explored two competing global drives: on the one hand, to modernize and advance, and on the other hand, to preserve a sense of cultural identity. His next book, The World Is Flat (2005), was an introduction to the accelerating process of economic globalization — and itself became a global bestseller.

Hot, Flat, and Crowded may be Friedman’s most compelling book yet. Building on his previous work, he takes aim at two large subjects. The first is the state of America—a nation that for many decades has overspent and underinvested, and that has squandered its power and its moral capital. The second is the state of the world. The planet is rapidly consuming its finite (and dirty) resources, even as the economic vitality of developing countries makes demand for those resources exponentially more intense. At the same time, global warming—the result of these same forces—portends an environmental crisis of unprecedented scope.

Is there a way out—for America as well the world? Friedman argues that the solution for one is the solution for the other — that the United States can and must take the lead in “innovating clean power and energy-efficiency systems and inspiring an ethic of conservation toward the natural world.” He is under no illusions that America is yet ready to take on this challenge. He is confident that it can—and that in doing so we will put ourselves and the rest of the planet on the right track.

In other hands, this diagnosis and prescription could be dreary and unremitting. Friedman brings to the task the skills of a master story-teller and consummate phrase-maker. Hot, Flat, and Crowded makes a provocative case for what is certain to be a global audience.

– Cullen Murphy, 2009 finalist judge

Editor at Large of Vanity Fair

2008 Nonfiction runner-up for Are We Rome?

Can citizens be helped to understand the fundamental workings of the world? Thomas Jefferson was not optimistic — though he knew that the American experiment depended on it. “Convinced that the people are the only safe depositories of their own liberty,” he wrote, “and that they are not safe unless enlightened to a certain degree, I have looked on our present state of liberty as a short-lived possession unless the mass of the people could be informed to a certain degree.” The record since Jefferson composed those words, in 1805, has been decidedly mixed. And in the 21st century, the question of whether Americans can be “informed to a certain degree”—about the environment, about the world economy, about constitutional principles, about the judicious use of national power—before it is too late remains an open one.

No journalist has been more assiduous in attempting to explain the world — not just to Americans, but to people everywhere — than Thomas Friedman of The New York Times. His book The Lexus and the Olive Tree (1999) explored two competing global drives: on the one hand, to modernize and advance, and on the other hand, to preserve a sense of cultural identity. His next book, The World Is Flat (2005), was an introduction to the accelerating process of economic globalization — and itself became a global bestseller.

Hot, Flat, and Crowded may be Friedman’s most compelling book yet. Building on his previous work, he takes aim at two large subjects. The first is the state of America—a nation that for many decades has overspent and underinvested, and that has squandered its power and its moral capital. The second is the state of the world. The planet is rapidly consuming its finite (and dirty) resources, even as the economic vitality of developing countries makes demand for those resources exponentially more intense. At the same time, global warming—the result of these same forces—portends an environmental crisis of unprecedented scope.

Is there a way out—for America as well the world? Friedman argues that the solution for one is the solution for the other — that the United States can and must take the lead in “innovating clean power and energy-efficiency systems and inspiring an ethic of conservation toward the natural world.” He is under no illusions that America is yet ready to take on this challenge. He is confident that it can—and that in doing so we will put ourselves and the rest of the planet on the right track.

In other hands, this diagnosis and prescription could be dreary and unremitting. Friedman brings to the task the skills of a master story-teller and consummate phrase-maker. Hot, Flat, and Crowded makes a provocative case for what is certain to be a global audience.

– Cullen Murphy, 2009 finalist judge

Editor at Large of Vanity Fair

2008 Nonfiction runner-up for Are We Rome?

My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for his Father’s Past by Ariel Sabar (Algonquin)

Traveling with his father to a remote corner of war-torn Iraq in a quest for roots and reconciliation, Sabar shares an intimate story of tolerance and hope in an Iraq very different from the one in the headlines today.

A Crime So Monstrous: Face to Face with Modern Day Slavery by Benjamin Skinner (Free Press)

Based on years of reporting in such places as Haiti, Sudan, India, Eastern Europe, The Netherlands, and, even suburban America, Skinner has produced a vivid testament and moving reportage on the horrors of contemporary slavery.

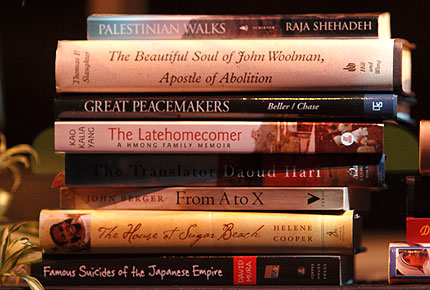

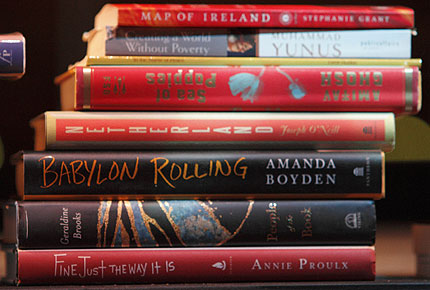

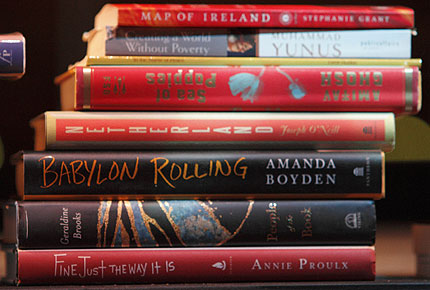

1. A Golden Age by Tahmima Anam

2. Babylon Rolling by Amanda Boyden

3. Beijing Coma by Ma Jian

4. Exiles by Ron Hansen

5. Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire by David Mura

6. Fine Just the Way It Is by Annie Proulx

7. From A to X: A Story in Letters by John Berger

8. Happy Family by Wendy Lee

9. How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone by Sasa Stanisic

10. Map of Ireland by Stephanie Grant

11. Netherland by Joseph O’Neill

12. Peace by Richard Bausch

13. People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks

14. Say You’re One of Them by Uwem Akpan

15. Sea of Poppies by Amitav Ghosh

16. Song Yet Sung by James McBride

17. Telex from Cuba by Rachel Kushner

18. The Boat by Nam Le

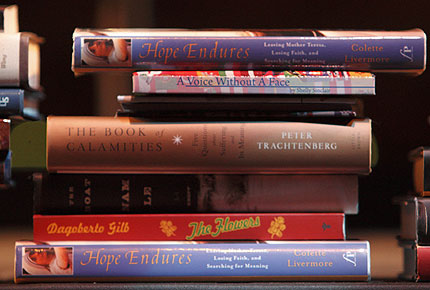

19. The Flowers by Dagoberto Gilb

20. The God of War by Marisa Silver

21. The Plague of Doves by Louise Erdrich

22. The Story of a Marriage by Andrew Sean Greer

23. The Torturer’s Wife by Thomas Glave

1. Crime so Monstrous by E. Benjamin Skinner

2. A Deadly Misunderstanding by Mark D. Siljander

3. A Voice Without a Face by Shelly Sinclair

4. Art and Upheaval: Artists on the World’s

Frontlines by William Cleveland

5. Creating A World Without Poverty by Muhammad Yunus

6. Dictionary of Homophobia by Louis-Georges Tin

7. Dust from our Eyes: An Unblinkered Look at

Africa by Joan Baxter

8. Finding Beauty in a Broken World by Terry Tempest Williams

9. Ghost Train to the Eastern Star by Paul Theroux

10. Great Peacemakers by Ken Beller and Heather Chase

11. Hope Endures by Colette Livermore

12. Hot, Flat and Crowded by Thomas Friedman

13. Human Smoke by Nicholson Baker

14. I Live Here by Mia Kirshner, J.B. MacKinnon, Paul Shoebridge, Mike Simons

15. In the Name of Peace by Uzeir Huskic

16. King by Harvard Sitkoff

17. Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and The Path to War in Vietnam by Gordon Goldstein

18. My Father’s Paradise by Ariel Sabar

19. My Life as a Traitor by Zarah Ghanhramani

20. Palestinian Walks by Raja Shehadeh

21. The Beautiful Soul of John Woolman by Thomas Slaughter

22. The Book of Calamities by Peter Trachtenberg

23. The Challenge by Jonathan Mahler

24. The Corpse Walker by Lio Yiwu, translated by Wen Huang

25. The Cuba Wars by Daniel P. Erikson

26. The Dancer From Khiva by Bibish

27. The Great Experiment by Strobe Talbott

28. The House at Sugar Beach by Helene Cooper

29. The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir by Kaokalia Yang

30. The Race Card by Richard Thompson Ford

31. The Translator: A Tribesman’s Memoir of Darfur by Daoud Hari

32. Whatever It Takes; Geoffrey Canada’s Quest to Change Harlem and America by Paul Tough

33. When the Prisoners Ran Walpole by Jamie Bissionette with Ralph Hamm, Robert Dellelo, and Edward Rodman

34. Writing in the Dark by David Grossman

Fred Arment, Novelist and a founder of the Dayton International Peace Museum

Adrienne Cassel, Reader for the Antioch Review; Assoc. Professor of English, Sinclair Community College

Michael Czyzniejeski, Editor in Chief of the Mid-American Review, Professor of English, Bowling Green State University

Susan Elliott, Assistant Professor and Head of Public Services at Zimmerman Law Library, University of Dayton

Barbara Farrelly, Retired Professor of English, University of Dayton

Martin Gottlieb, Editorial Writer, Dayton Daily News

Lucrecia Guererro, Latina Writer; English Instructor, Purdue University

David Herrelko, Retired General, U. S. Air Force; Engineering Professor, University of Dayton

Tanya Higgins, Writer, Historian

Julia Hobart, Founder of The Overfield Early Childhood Program, Troy; Community Volunteer

George Houk, Graphic Artist, Nonfiction Writer

Pam Houk, Museum Educator, Writer

Lynette Jones, Professor of African American Literature, Wright State University

Trudy Krisher, Writer; Associate Professor Academic Foundations Department, Sinclair Community College

Peggy Lindsey, Lecturer in English, Wright State University

Nancy Lupo, ESL specialist, Community Volunteer

Margarite Merz, Director of Corazon; Master of Theological Studies, Harvard Divinity School; Master of Divinity, St. Leonard College; Doctor of Ministry, Graduate Theological Foundation

Gary Mitchner, Professor Emeritus, Sinclair Community College; Poet

Jack O’Gorman, Coordinator of Reference, University of Dayton Library; Editorial Board of Booklist

Vanessa Perez, Associate professor in Comparative Literature with emphasis on Latina Literature, Brooklyn College

Larry Rab, Retired attorney

Paul Rab, Professor Emeritus, Sinclair Community College; specialist in military history

Mike Rose, Book Buyer for Books & Co.

Linda Skuns, Community Volunteer

Gordon Lish

was founder and editor of The Quarterly, Vintage Books, thereafter the Rosenkranz Foundation from 1986 to 1996. He was an editor at Alfred A. Knopf from 1977 to 1995. He was fiction editor of Esquire from 1969 to 1977. In the ‘60s, he was the editor and founder of the literary magazines The Chrysalis Review and Genesis West, the latter of which associated itself with the fiction of Ken Kesey, the marvels of Neal Cassady, and the poetry of Jack Gilbert.

He is the author of the novels Dear Mr. Capote, Peru, Extravaganza, My Romance, Zimzum, Epigraph, and Mourner at the Door, Selected Stories, Self-Imitation of Myself, Sounds in American Fiction, The Secret Life of Our Times: with an introduction by Tom Wolfe, and All Our Secrets Are the Same.

Mr. Lish has taught imaginative writing at Yale, Columbia, and New York University, and is known for his many years of presenting private classes, sessions of which were six to ten and a half hours in duration.

He was a Guggenheim Fellow in 1984. Lish’s fictions have been anthologized in such standards as Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards, and Pushcart Prize, and he has contributed essays on Jewish matters to the books Congregation (HBJ) and Testimony(Times Books).

Lish is thought to be a figure of controversy; his activities—as teacher, writer, editor, publisher—have been the subject of scores of newspaper and magazine articles, of television appearances, and, in the early ‘90s, of a litigation wherein he opposed Harper’s on a question of copyright infringement, and prevailed.

He is generally described as our foremost teacher of creative writing, and in respect of his latest book, Kirkus said “Lish is our Joyce, our Beckett, our truest modernist”.

In November of 1994, Le Nouvel Observateur cited Lish as “one of the one hundred major writers of our time.”

Katherine Vaz

a Briggs-Copeland Fellow in Fiction at Harvard University and a 2006-7 Fellow of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, is the author of two novels, Saudade (St. Martin’s Press), a Barnes & Noble Discover New Writers selection, and Mariana in six languages and picked by the Library of Congress as one of the Top 30 International Books of 1998. Her collection Fado & Other Stories won the 1997 Drue Heinz Literature Prize, and Our Lady of the Artichokes won the 2007 Prairie Schooner Book Prize. Her fiction and essays have appeared in numerous magazines and her children’s stories has been published in anthologies from Viking and Simon & Schuster.

Gerald Early

is the Merle Kling Professor of Modern Letters in the English Department at Washington University in St. Louis. He also holds an appointment in the African and Afro-American Studies Program, for which he served as director for eight years, from 1991 through 1998. He is currently the director of Center for the Humanities, formerly known as the International Writers Center started by philosopher/novelist William Gass in 1991.

Professor Early has published several books including Tuxedo Junction: Essays on American Culture and The Culture of Bruising: Essays on Prizefighting, Literature, and Modern American Culture, which won the 1994 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. He has also published One Nation Under a Groove: Motown and American Culture and Daughters: On Family and Fatherhood. He is currently working on a book about African Americans during the Korean War era as well as a novel about jazz for young people entitled “Up For It.” His latest book is called This is Where I Came In: Essays on Black America in the 1960s, a collection of three lectures published by the University of Nebraska Press.

Cullen Murphy

is the editor-at-large of Vanity Fair magazine. He was previously, for two decades, the managing editor of The Atlantic Monthly. Before that he was a senior editor at The Wilson Quarterly. In addition to his work as a magazine editor Murphy for twenty-five years wrote the comic strip Prince Valiant, which was drawn by his father, the illustrator John Cullen Murphy. Murphy’s articles and essays have appeared in many publications, including The Atlantic Monthly, where he wrote a monthly column, Harper’s, The New Republic, Slate, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, American Heritage, and Smithsonian. His books include The Word According to Eve (1998), about women and the Bible; Just Curious(1995), a collection of essays; and Rubbish! (1992, with William L. Rathje), an anthropological study of garbage. He is currently at work on a book about the Inquisition.

Professional activities aside, Murphy is involved in the work of many organizations. He is a member of the board of trustees of Amherst College, and serves on the board of the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Emily Dickinson Museum, and the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities. He is also on the editorial board of The American Scholar and of OnEarth, the magazine of the Natural Resources Defense Council, and he is a member of the usage panel of The American Heritage Dictionary.

In 2008 Murphy was the runner-up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Nonfiction.

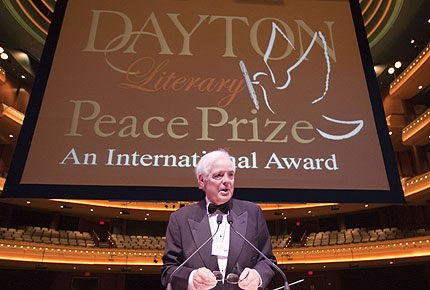

The 2009 Awards Ceremony was held at 5:00 pm on Sunday, November 8th, 2009, at the Benjamin and Marian Schuster Performing Arts Center at One West Second Street in Dayton, Ohio. Nick Clooney was the Master of Ceremonies.

Lifetime Achievement Award Nicholas Kristof & Sheryl WuDunn

Fiction Award Richard Bausch for Peace

Nonfiction Award Benjamin Skinner for A Crime So Monstrous: Face to Face with Modern Day Slavery

Fiction Runner-up Uwen Akpan for Say You’re One of Them

Nonfiction Runner-up Thomas Friedman for Hot, Flat and Crowded

Photos by Andy Snow (andysnow.com) ©2009.

As a television newsman, Nick has been reporter, anchor, managing editor and news director in Lexington, Cincinnati, Salt Lake City, Buffalo and Los Angeles.

As a columnist, Nick has, since 1989, contributed three columns a week to the Cincinnati and Kentucky Post dealing with subjects as varied as politics, travel, music and American history. Some of his articles and op-ed pieces have appeared in newspapers around the country, including the Los Angeles Times and the Salt lake Tribune.

As an author, he has published three books, including The Movies That Changed Us in 2002.

But the curiosity that drove Nick to a life as a reporter, also led him to explore other areas of interest. He hosted talk shows in Cincinnati and Columbus and music programs on radio. For five years he was a writer and daily on-air spokesman for American Movie Classic cable channel. Now, he is a writer, producer and host for American Life cable channel. His Moments that Changed Usprogram explores the intersection of a person and an important moment in our history. Guests have included John Glenn, Walter Cronkite, Diahann Carroll and Steve Wozniak.

Nick began working on radio full time when he was 17, in his hometown of Maysville, Kentucky.

In addition to his continuing broadcasting career, Nick has been a speaker, master of ceremonies or panelist of more than 3,000 events coast-to-coast.

Nick has accumulated a number of awards and honors over the years, including an Emmy for commentary and three Emmy nominations for his work on American Movie Classics. In December 1998, he received an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from Northern Kentucky University. In 2000, he received the President’s Medal from Thomas More College, and was inducted into the Cincinnati Journalism Hall of Fame. In 2001, Nick was inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame. In 2005, he was inducted into the Ohio Television Hall of Fame. In May 2007, Nick received an honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of Kentucky and was the commencement speaker, a task he has undertaken at 31 other schools over the years.

Nick is married to Nina Warren of Perryville, Kentucky, who is a writer, inventor and TV host. Their oldest child, Ada, also a writer, is the mother of the World’s Only Grandchildren, Allison and Nick. The Clooney’s younger child, George, is an Oscar-winning actor, producer, writer and director in films.

In April of 2006, Nick and his son George went to the Sudan and Chad to report on the ongoing genocide in the region of Darfur. Since their return, both have traveled extensively as advocates for a peaceful solution to the crisis. George has spoken at the United Nations and has traveled to China and Egypt. He continues to hold fundraisers, while Nick has made more than 75 speeches at schools, churches, and town meetings. The pair has also made a documentary, Journey to Darfur, which has been shown internationally.

In the early 1970s, Nick and Nina decided to establish a permanent home from which they could travel according to the demands of their peripatetic profession. They moved to the beautiful river town of Augusta, Kentucky. Both of their children graduated from tiny Augusta High School. Eventually, other members of the family found their way to Augusta, including Nick’s famous sister, Rosemary Clooney. After her death in 2002, Rosemary’s home became a museum honoring her career.

Advancing years sometimes dictate a slow-down in professional activity. Someone forgot to tell Nick. He is currently the “distinguished journalist in residence” at the American University in Washington D.C. through the partnership between the school and the Newseum, a 250,000-square-foot museum in Washington dedicated to news. He’ll teach opinion writing this fall and a spring course based on his 2002 book, Movies That Changed Us.