Written by Amariá Jones

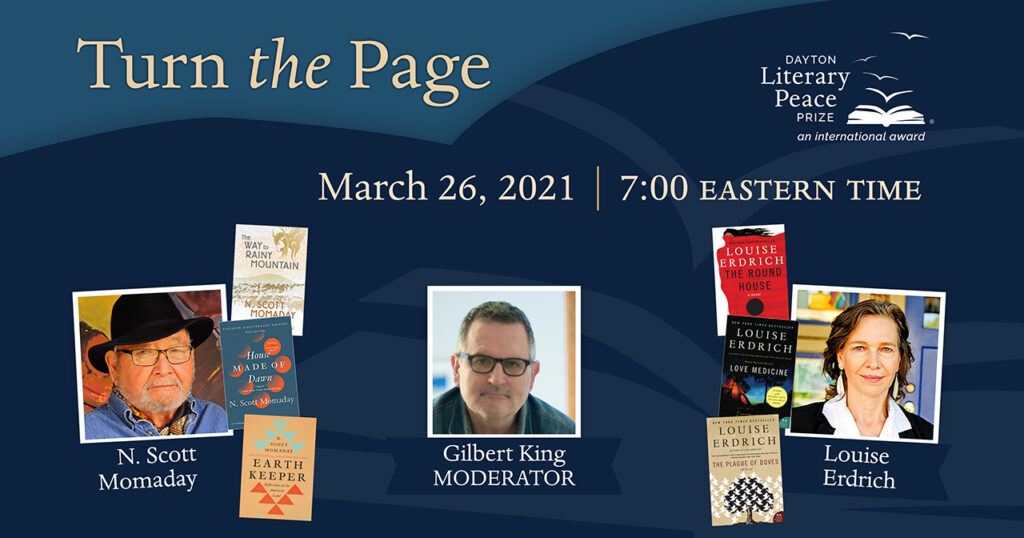

Scott Momaday – Pulitzer Prize winner | Louise Erdrich – 2014 Holbrooke award (DLPP) & Independent bookstore owner | Gilbert King- Facilitator

In this virtual gathering of writers, Gilbert King, author of Devil in the Grove and 2013 Dayton Literary Peace Prize Runner up sits down with authors N. Scott Momaday and Louise Erdrich to discuss land, loss, and memory from the perspective of indigenous writers.

As the panel begins, author Louise Erdrich greets the audience in her native tongue, acknowledging both her tribe and the land from which they originate. As both authors settle in, King asks them to describe the relationship with land that they hope the readers are able to grasps from their novels. Erdrich focuses mostly on the generational transitions made by Indigenous peoples as land ownership became destabilized by colonization. She explains that although these traditional techniques of living off of the land are no longer practiced on a large scale, they have been passed down throughout generations for the sake of preservation. Momaday agreeing with Erdrich wants readers to understand and acknowledge the Native American relationship to land. He believes that we must be concerned with all parts of nature, whether Native or not. More than anything, he believes that we must understand the land as Spirit.

Both authors acknowledge the contrast of relationship with land between Indigenous peoples and European colonizers. Louise Erdrich explains that the relationship between indigenous people and the land served as a vast conflict between them and the Europeans. She states, “There was no concept of personal ownership, but a spiritual relationship based on humility, need and love.” She believes that the type of need that she mentions can be best described as the relationship a child has to its mother.

King later mentions some of the authors’ works that focus on land, lack of ownership, and governmental policies. Quoting from the novel of Momaday’s Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land King quotes, “The earth does not want shame, it wants love.” He then asks Momaday to explain what this type of love would look like at the present moment. Momaday expresses a focus on salvation. He answers, “Conversation, preservation and understanding that the earth is alive and is posses of spirit.” We must first understand that the land that we walk upon and extract resources from is alive, and we are unable to live upon it without practicing reciprocity. Momaday states, “It is indeed the landscape of memory; it’s never going to be again what it was once, so we have to live vicariously in terms of it…understanding it is history and something that has happened in the past.” In recognizing this past, Momaday also addresses our current responsibilities. He believes that we must pay attention to the land, while also appreciating that past values that have helped to inform the land.

In a later conversation surrounding land and leadership. King asks the authors opinions of Deb Haaland, who became the nation’s first Native American cabinet secretary in the Department of the Interior. Both authors described themselves as ecstatic and overjoyed. Momaday hopes that a greater understanding or relationship between man and earth will be cultivated while Haaland is in office; while Erdrich hopes that Haaland’s personal insight will influence those around her to also take a look at the science. Erdrich hopes that Haaland’s time in office will help others to realize how gracious the earth has been to us; ultimately decolonizing our minds of ownership and possession of what comes and is given freely.

As King refocuses on the idea of land and community, he speaks with Erdrich about the many epidemics taking place within Native communities. He asks her to expound on the sexual assault and violence faced by Native women on reservations as well as throughout the nation. She states, “I believe in the changing of hearts and minds, but I also believe that there is evil… and women are victims of this particular evil.” She explains that so many Native women are lost to brutality. She believes that justices cannot be served until there is funding, law making, and most importantly sovereignty given to tribal courts. She explains that allowing tribal courts to serve justice on tribal issues is of grave concern to the Native community, and it has not yet been granted.

However, Native peoples have also been deeply affected by the results of the COVID-19 pandemic. She explains that Native communities are two times more likely to lose individuals within their communities opposed to non-native peoples. Moreover, those who are being lost to the virus serve as integral parts of the Indigenous communities. Many traditional people and spiritual leaders have been lost to the pandemic, and this lose can be felt wide and large throughout the community.

As King concludes the panel, he revisits the authors previous quotes given to the organization about peace and literature. He asks them whether or not they believe in hope for the future.

Momaday says there is. He says, “Literature is a function of the imagination related to peace, tranquility, and harmony in the world. He continues to say, “Literature is a kind of bridge between the past and the present. The darkness of the past and the promise of the present and the future.” This hope in literature and the gaps that are bridged can also be heard in Erdrich’s statement on ‘collective awareness.’ She believes in the power of art; she says that it “leads us toward conciliation with our humanity…revealing ourselves to one another. This revealing of self allows for truth which Erdrich believes will help to create our common story.

It is when we admit to our folly, our recklessness, and even our most destructive actions that we are able to see truth and create a common story written in the ink of authenticity.

Each year, DLPP has interns who have been working on major projects throughout the fall. The application process is competitive, and the DLPP has worked with professors at Sinclair College, University of Dayton and Wright State University to design intern projects that will be valuable to both the student and the DLPP.

Amariá C. Jones, the 2021-2022 intern from the University of Dayton, is pursuing a BA in English and Creative Writing. She has been the administrative assistant at the Roesch Library at UD; was inducted into Sigma Tau Delta, the international English honor society; is the historian for Black Action Through Unity, and numerous other groups focusing on inclusion and community here in Dayton and beyond; was an intern at the Greater Washington Urban League in Washington, DC; and valedictorian of her high school class. She will be doing data collection and writing a blog for DLPP as well as assisting with DLPP community events and other DLPP projects.University of Dayton interns now earn course credit for their work through ENG 485: Writing Internship, a hybrid course that meets just several times over the semester. This gives students the chance to share skills they’ve gained with each other and form a valuable network to learn about opportunities within the community.