Written by Amariá Jones

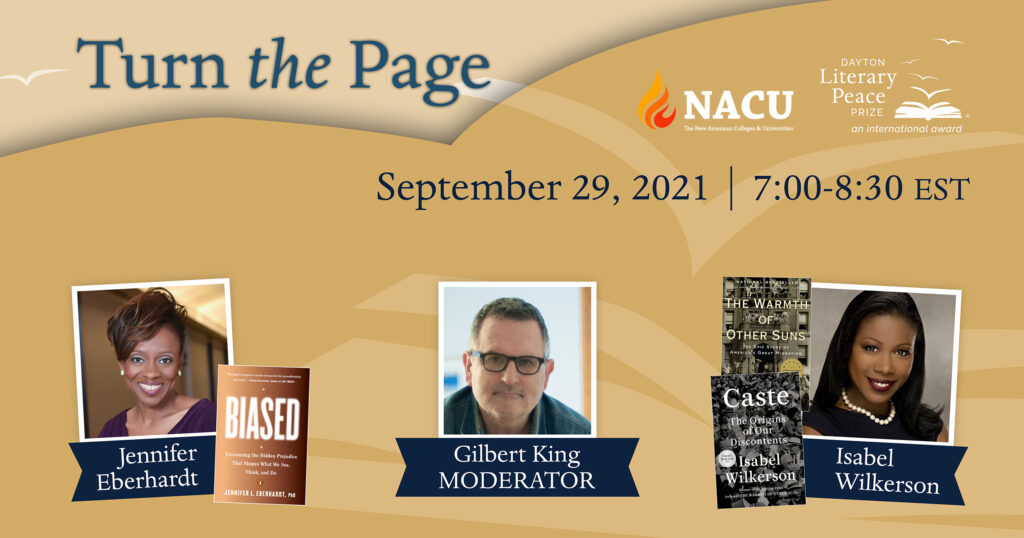

Isabel Wilkerson – Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent | Jennifer Eberhardt – Biased, Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do | Gilbert King- Facilitator

In this virtual gathering of writers, Gilbert King, author of Devil in the Grove and 2013 Dayton Literary Peace Prize winner sits down with authors Isabel Wilkerson and Jennifer Eberhardt to discuss ‘caste, class, race, and bias,’ through the lens of their latest works.

Isabel Wilkerson DLPP 2021 finalist, and author of Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent, begins the conversation by providing a working definition for the title of her book. Wilkerson links the terminology of caste to both systematic hierarchies and the larger conception of American racism. She defines it as, “An arbitrary artificial ranking in human society…[and] The defining factor of one’s worthiness through categorization.” This definition lays the foundation for Wilkerson’s work, which focuses on the American Jim Crow era, and its rigid boundaries that limited the livelihood of African-Americans from the late 1870’s until the early 1960s. As Wilkerson explains the vast influence of racially motivated caste systems in America, author and Professor Jennifer Eberhart gives the audience a greater understanding of implicit bias.

Eberhardt defines it as, “A perception and attitude that determines decision making—even when one is unaware.” In her book, Biased, Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do, Eberhardt takes a deep dive into the topic of prejudice and predictable patterns. She explains that “reliance on predicable patterns allow us to move through the world in an efficient way.” It is the idea that the very biases that are trusted to help us, possess the same capability to blind us to what is real.

In both books these authors deal with the history of American racism and its impact on our societal norms and cultural misconceptions. Wilkerson discusses the consequences of “codification,” and how decades of repetition have created racist self-operating machines that no longer need our participation. She explains that with or without the law, it is the implicit bias that keeps these systems in place. The idea is that although laws may be the origin of these systems, biases held by individuals keep them in motion. Ultimately, once set into motion these biases act as electrical currents, holding these systems in place. Jennifer Eberhardt agrees, she says that there are no specific laws that we must focus on changing, but our implicit biases that become the main focus.

As the discussion continues, King questions the authors about the importance of storytelling. He asks, “Can you tell the story of racism without telling the story of specific horrific incidents?” Ultimately, the short answer is no. Eberhardt believes that stories are needed to avoid the possibility of becoming foolish. In the barrowing and retelling of these horrific events, the importance of guidance and context must be noted. However, to completely relinquish the power and experiences of others—leaving the acknowledgment of their struggles up to memory—would be the quickest way to forget what those before us have endured.

Wilkerson amplifies this truth by mentioning the importance of technology in this process. It is no surprise that we now have the ability to record, repost, retweet, and forward the things we capture on our smartphones. However, Wilkerson believes that such technology can sometimes serve to do more harm than good. Take for example the killing of George Floyd which happened during the earlier half of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although recorded for good reason, and later used as damning evidence; this video was replayed throughout the interweb for months after the incident. How long does it take before such visuals become dishonoring to the stories of these victims? How much sooner do onlookers become desensitized to these events captured on film upon realizing that they can be searched up at any minute? These are the types of questions that Wilkerson wants the audience to consider. She wants us to understand the process of capturing brutality. Ultimately, she explains that it is the concept of showing and not telling that the author must master, and this process takes lots of time and research.

As America continues to come face-to-face with its racial past, Jennifer Eberhardt said that it becomes important to, “be aware of what is happening now.” However, this cannot be successful accomplished without recognizing how our country’s past informs its present. Eberhardt furthers her point by explaining that when one is unaware of their previous history, there is no easy way to gain understanding of modern inequalities.

While the authors continue to converse around such topics, King poses another question that largely focuses on possible solutions. He asks, “is there a pathway that leads towards unity, and away from racism and bias?” Eberhardt answers immediately, she explains that it the written word that helps people understand the importance of such topics. Wilkerson follows with a different perspective, she explains that we must understand the roles of the American ‘legal, social, and governmental frameworks,’ and she believes that they all play a part in the lack of unity found within this country. Ultimately, the debunking of false teachings and narratives would largely aid in bringing this country’s citizens closer to the unity so many of us desire.

So how should this knowledge of such history be sought after? How do we as a country add more seats to this table? Wilkerson uses the analogy of moviegoers who are late to the showing of their film. She states, “Many of us have no idea as to what has taken place.” She talks about the crucial aspect of listening, rewinding, and rewatching. She concludes her point by stating, “[it is] only when you go back to the beginning of the movie [that] you understand what has happened.”

Through the capturing and representing of these histories, and the lengths that authors must go to preserve what is sacred, one can only wonder the physical, emotional, and even spiritual toil such documentation can create. Gilbert King focuses in on these aspects by asking the authors about self-care during these long stints of writing. Eberhardt puts it this way; she says she feels, “empowered by the research that is done.” She explains that through taking on these projects she learns things that are of use and that bring peace. Both Eberhardt and Wilkerson agree that by completing this work, the feel that they have fulfilled a duty and hope that they have both ‘soothed’ and, or ‘relieved,’ the families to whom this history belongs.

As the discussion reaches its concluding point, King questions the authors about “teacher preparation” and discussions around racial biases. Wilkerson answers this question by focusing on the future. She askes the audience to wonder about the future, and the dangers that it might hold if we as a country put a halt to well-rounded educational practices. She explains that doing so would consequently affects some communities more than others, mostly because some children in America do not have to luxury of not knowing their history. Eberhardt agree with Wilkerson, while also reemphasizing the importance of understanding the world that we live in now.

As the authors conclude their time with King, they share with him their next steps. Isabel Wilkerson hopes to embark on a now virtual book tour due to limitation presented by the COVID-19 pandemic; Jennifer Eberhardt plans to continue a smaller series of books focused on disrupting biases amongst parents and educators, while also focusing on her organization SPARK which focuses on addressing social issues through various mediums.

Each year, DLPP has interns who have been working on major projects throughout the fall. The application process is competitive, and the DLPP has worked with professors at Sinclair College, University of Dayton and Wright State University to design intern projects that will be valuable to both the student and the DLPP.

Amariá C. Jones, the 2021-2022 intern from the University of Dayton, is pursuing a BA in English and Creative Writing. She has been the administrative assistant at the Roesch Library at UD; was inducted into Sigma Tau Delta, the international English honor society; is the historian for Black Action Through Unity, and numerous other groups focusing on inclusion and community here in Dayton and beyond; was an intern at the Greater Washington Urban League in Washington, DC; and valedictorian of her high school class. She will be doing data collection and writing a blog for DLPP as well as assisting with DLPP community events and other DLPP projects.University of Dayton interns now earn course credit for their work through ENG 485: Writing Internship, a hybrid course that meets just several times over the semester. This gives students the chance to share skills they’ve gained with each other and form a valuable network to learn about opportunities within the community.