Written by Grace Pierucci

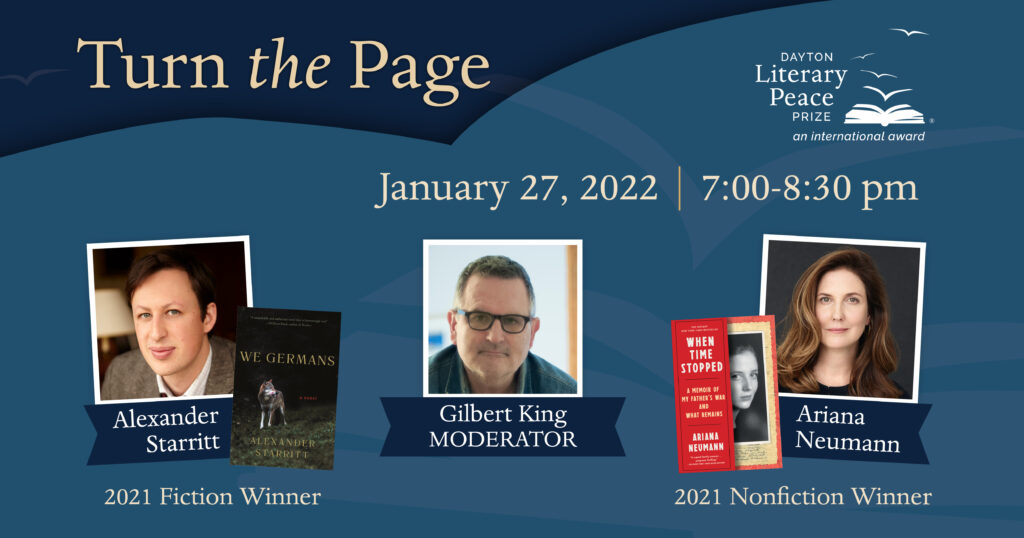

Alexander Starritt – We Germans | Ariana Neumann – When Time Stopped: A Memoir of My Father’s War and What Remains | Gilbert King- Facilitator

The sixth Turn the Page event, moderated by Gilbert King, features a conversation between Alexander Starritt, the 2021 Fiction Winner for We Germans, and Ariana Neumann, the 2021 Nonfiction Winner for When Time Stopped. Their works take place during the Second World War, both focusing on characters who are not necessarily heroes, but who did what was necessary for survival. They discuss how novels centered around war can be about peace, how individual histories (both fictional and non-fictional) can bring about understanding, and they delve into themes of personal identity within a totalitarian society. Historians today are still grappling over the extent to which the majority of German citizens understood the atrocities taking place, and societies are both beginning and continuing to recognize past atrocities, making this discussion incredibly relevant today.

Ariana Neumann’s book is a product of her own research into her father, telling the story of a daughter making peace with her relationship with her father and finding understanding. In this way, her story set during a war is also a story of peace. Alexander Starritt, similarly, illustrates this notion of understanding through the realization the German soldiers have. “They understand on some level they ought to lose the war”. There is a moment when they have to come to terms with what is happening and understand that they are on the wrong side of history. Through these war stories, both authors produce narratives of understanding, a key aspect of peace.

Neumann explains how her research created a new understanding of her father. It is difficult for us to imagine our parents as they were and beyond our own relationships with them. While her perception of her father was generally rigid, strict, and punctual, she began encountering anecdotes of him as a boy that portrayed him in a whole new light. His family was deported into camps, but he escaped by acquiring a fake id and moving to Berlin. He worked in a Nazi factory there, doing what he could to survive. Learning from this story provides an opportunity for his daughter to better understand him and come to terms with their relationship. He was not a hero or a martyr but did what he could to survive. His story of survival was not one he wished to discuss and was left to Neumann to discover and tell.

When asked if they thought their story wanted to be told Neumann answered that she does believe in fate and magic, bringing up her Venezuelan heritage. As a young girl, she always wanted to be a detective and enjoyed solving mysteries. She and her father would solve puzzles together and he knew that she liked piecing together information. Leaving her with a box containing clues and information about the parts of his life he did not mention was “his way of saying, this is a story”. Neumann also explains how boxes would arrive at her house with more clues, such as one from the man living in what was her grandparents’ house. She emailed him asking a few questions and he responded saying he could send her the contents of her grandparents’ safe. There are stories that need to be told.

When asked how anyone can grasp such horror as what took place during the war, Starritt responds by saying that it was a gradual process and discusses a type of spectrum. The debate as to how much knowledge people had about what was happening is too binary for Starritt. This line of questioning leads to an “implied crossover point of knowledge”, where above this line you are guilty and below you aren’t culpable of the horrors that took place. There is really a “spectrum of knowledge”. He says even a simple farmer, far from the concentration camps, is producing grain that is feeding Nazi factory workers and soldiers. “The nature of a totalitarian society is that there is no neutral ground. Totalitarianism removes the luxury of not being involved.” Furthermore, Starritt emphasizes the gradual nature of the realization that what was happening was beyond the normal spectrum of the acceptable behavior of states. Different individuals will come to this realization at their own pace and deal with it in their own ways. Neumann highlights the importance of Starritt’s point; that recognizing evil is gradual. She says rights were slowly taken away from Jewish people. “At some point, you think it’s not right, but is it when they take your umbrella or make you wear a gold star?” Neumann says that when immersed in horror it is hard for individuals to do anything about it. The scale of it all and the atrocities were unimaginable. Both authors acknowledged the importance of avoiding stark categories of good and evil, instead recognizing everyone is human with the propensity for both good and evil action.

Building off of these ideas, Starritt explained that the more distanced events in history are from the present, the easier it becomes to make these generalized categories of heroes and villains. He says these terms do not explain human behavior. A better model for describing people is by their moral dimensions instead of grouping them into these two generalized camps. Many people were just trying to survive during the war. Someone could be doing evil during the day and come home to be a loving parent. He says the best explanation for the German collective sense is about shame, rather than guilt. It is more effective and useful to be ashamed of one’s actions than guilty. Language should move beyond labeling people as good and evil.

Neumann brought up the Auschwitz trials, which were under German rule, and tried people based on if they were cruel beyond their orders. People were doing what they could to survive, and therefore she agrees that shame is more useful than collective guilt. She clarifies that there is still evil in the world and some individuals who are guilty, but uses a German man as an example as to why collective guilt is not productive. A German man told her he was ashamed of his German passport. He was not alive during the war and she said the guilt should not trickle down to him as an individual. Starritt continued this reasoning stating that the Auschwitz trials are an example of a way to approach historical individuals. There is a baseline of expectations in society that gives moral context to their actions. That baseline can be evil, such as owning slaves, but the moral context allows one to examine how the individual deviated from it. How did George Washington, for instance, break from that norm? Was he a horrific slaveowner or a kind one?

Starritt’s work delves into these types of dilemmas of identity. He writes about soldiers becoming sure they will lose the war and coming to understand that they should. He encapsulates that moment of realizing one’s self is on the wrong side of history. “It’s not about supreme ends of a spectrum, it’s about a broad mass of complicit people part of that society”. It is important for societies to reexamine their histories today and to ask the question of how we deal with national heroes doing evil deeds.

War stories have the ability to bring up such questions, expose the dangers of generalizations, and bring about a greater sense of understanding. Alexander Starritt and Ariana Neumann examine these questions of identity through characters on different sides of history. Although one focuses on the Jewish experience and one on that of German soldiers, both focus on those who were not heroes, who were simply surviving in a totalitarian regime, and who struggled with their shame. These stories do not need harrowing acts of bravery and all the pomp and circumstance associated with heroes because they bring about peace through their honesty.

Each year, DLPP has interns who have been working on major projects throughout the fall. The application process is competitive, and the DLPP has worked with professors at Sinclair College, University of Dayton and Wright State University to design intern projects that will be valuable to both the student and the DLPP.