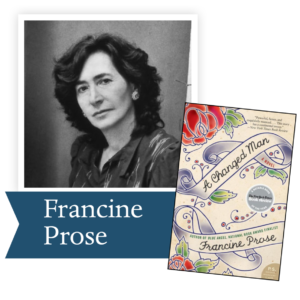

Francine Prose grew up in Brooklyn and attended Radcliffe College, where she majored in English Literature and from which she graduated in 1968. She briefly attended graduate school in Medieval English literature, then left Harvard to live for a year in India, where she began to write her first novel, Judah the Pious. Upon returning home, she sent her novel to a former writing teacher who in turn forwarded it to the legendary editor Harry Ford, then at Atheneum. He bought the book immediately, and it was published when she was 26.

Since then, Prose has written 13 novels, among them Bigfoot Dreams, Primitive People, Household Saints, which was made into a 1993 film directed by Nancy Savoca and starring Lili Taylor, Tracey Ullman and Vincent D’Onofrio, Blue Angel, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, and most recently A Changed Man. Her short story collections include Women and Children First and The Peaceable Kingdom; she has also published three books of translation and a collection of novellas, Guided Tours of Hell. She has written five books for children. Her most recent book was The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists They Inspired.

Her stories, reviews, cultural criticism and essays have appeared in such publications as The New Yorker, The New York Times, Atlantic Monthly, Art News, Elle, The Paris Review, and Tin House; she has written frequently on art for The Wall Street Journal. She is a contributing editor at Harpers Magazine, for which she has written such controversial essays as “Scent of a Woman’s Ink” and “I Know Why the Caged Bird Can’t Read.”

Prose is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, two NEA grants, two New York State Council on Arts grants, a PEN Translation Prize, and two Jewish Book Council Prizes. In 1989, she traveled throughout the former Yugoslavia on a Fulbright Creative Writing Fellowship. She has taught at Harvard, the University of Arizona, the University of Utah, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the Sewanee and Bread Loaf Writers’ Conferences. She is on the faculty of the New School MFA Program, a board member of PEN, a member of the New York Institute for the Humanities, and has been a Visiting Writer at the American Academy in Rome. She was one of the first recipients of a Director’s Fellowship at the New York Public Library’s Center for Scholars and Writers.

Francine Prose, the mother of two grown sons, lives in New York City with her husband, the painter and illustrator, Howard Michels.